In the Wake of the Quake—Relief for Myanmar

By Chiu Chuan Peinn (周傳斌)

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting (吳曉婷)

Photos by Wai Yan Htun

In the Wake of the Quake—Relief for Myanmar

By Chiu Chuan Peinn (周傳斌)

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting (吳曉婷)

Photos by Wai Yan Htun

A pagoda in the ancient city of Inwa, near Mandalay, was severely damaged by the earthquake. (Yi Mon Than)

Devastation

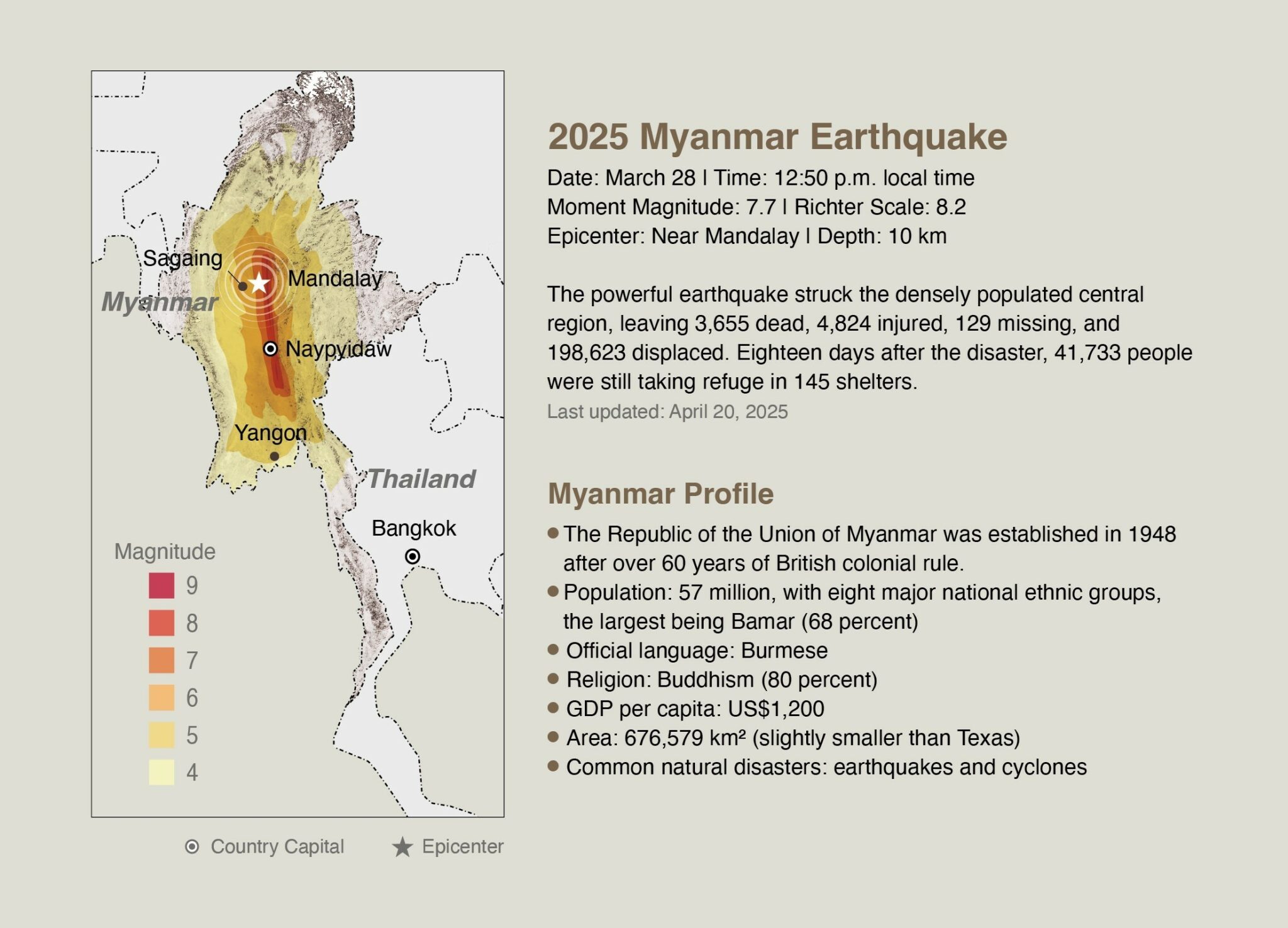

The earthquake resulted from a sudden release of accumulated stress along the Sagaing Fault, causing widespread devastation in the Sagaing and Mandalay regions.

Ma Soe Yain Monastery (photo 2) in Mandalay had long been a center for monastic education and a respected hub for Buddhist scholars from Myanmar and abroad. At the time of the earthquake, many young monks were taking a religious examination when the monastery collapsed, leading to heavy casualties. Thirty-nine people were reported killed. (Photo 2 by Kyi Moe Htet Kyaw)

Religion

Mandalay is one of the central hubs of Buddhist history in Myanmar, with its temples and stupas serving as exquisite examples of Buddhist artwork. Entering Mandalay feels like stepping into a Buddhist museum.

In the ancient city of Inwa, a former imperial capital at various times between the 14th and 19th centuries, more than 900 historic buildings, stupas, and temples were damaged in the quake. (Photo 2 by Yi Mon Than)

Trauma

The lack of heavy machinery available in the immediate aftermath of the disaster forced people to dig through the rubble by hand in an effort to reach those trapped beneath collapsed buildings. However, even when survivors were pulled from the debris, the severe shortage of medical resources meant that many could not receive timely treatment, contributing to a high death toll.

The main building of Mandalay General Hospital was declared structurally unsafe, prompting staff to set up canopies on the surrounding grounds to serve as temporary wards (photo 1). The hospital quickly became overwhelmed by the influx of casualties after the quake. Relief organizations responded by providing tents, setting up temporary shelters, and offering medical care (photo 2). (Photos by Yi Mon Than)

At 12:50 p.m. on March 28, Myanmar time, Jiang Rong Hua (姜榮華) was sitting in his car when it suddenly jolted, as if struck by a wave. He immediately realized it was an earthquake. Motorcyclists pulled over, and people fled their homes in panic. The shaking lasted nearly a minute—longer than any tremor Jiang had ever experienced. When it finally stopped, he stepped out of his car and comforted a crying resident, saying, "It's okay. You got out. It's safe here."

At the time, Jiang was in Mandalay Region and had yet to grasp the full scale of the disaster. According to the United States Geological Survey, the earthquake registered a moment magnitude of 7.7 and struck at a shallow depth of just ten kilometers (6.2 miles), giving it immense destructive force. The quake claimed thousands of lives.

That same day, Daw Thida Khin (李金蘭), head of Tzu Chi Myanmar and Jiang's niece, was visiting family in Taiwan with her husband. Like Jiang, she is an ethnic Chinese born and raised in Myanmar. Upon hearing about the quake, she anxiously contacted family members to check on their safety. Once she confirmed they were okay, she began coordinating the procurement and distribution of emergency supplies.

Jiang passed many collapsed buildings along the road as he drove home. His own house was in disarray but still standing, and his family was thankfully unharmed. With aftershocks continuing and fearing further damage, they gathered what they needed and prepared to sleep outside that night. Later that evening, Jiang walked until he could find a cell signal and received a call from Daw Thida Khin.

His niece asked him if he would find people to help collect and distribute relief supplies that had already been purchased. The next day, Jiang gathered friends and went to pick up the goods, which they delivered to Mandalay, the capital of Mandalay Region. Just 17 kilometers (11 miles) from the epicenter, Mandalay was among the hardest-hit areas. Upon arrival, they spent a long time negotiating with the military, which had sealed off the area, before finally being allowed in.

Once inside the disaster zone, Jiang was stunned into silence at the sight of the collapsed Sky Villa complex. "It was heartbreaking," he said. "There's no way to describe it—everything had collapsed…" Malaysian volunteer Cecelia Ong (王慈惟) visited the same site nearly two weeks later. She described the scene in more detail: "Three of the four buildings, each more than ten stories tall, were reduced to rubble. Half of the fourth structure had collapsed, with only four or five floors still standing."

For three days following the quake, Jiang delivered bread, bottled water, and functional beverages to rescue workers, hoping to support search efforts during the critical window for saving lives. But with the scorching heat, a lack of heavy machinery, and the vast scale of devastation, even the military government's rare appeal for international aid—and the arrival of search-and-rescue teams from other countries—did little to speed up the recovery efforts.

On April 11, volunteers arrived in Sagaing to assess the earthquake's damage. Here, two volunteers comfort survivor Htwe Htwe Lwin, who, despite mourning the loss of her siblings, donated rice to support other survivors.

Launching emergency relief

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the most urgent needs were clean drinking water, medical care, medicine, and emergency shelter. According to ReliefWeb, a United Nations humanitarian information service, the Myanmar Red Cross Society and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies responded swiftly by distributing pre-positioned supplies stored within the country. By mid-April, the World Health Organization had provided nearly 170 tons of medicine, medical equipment, and tents.

As international organizations responded on a broad scale, Tzu Chi also sprang into action. While Jiang delivered the foundation's first batch of relief goods, volunteers in other countries worked swiftly to prepare additional supplies. Liang Si-yu (梁思諭), who oversees Myanmar affairs at Tzu Chi's Department of Religious Affairs in Taiwan, quickly formed a task force with colleagues responsible for nearby regions. Together, they contacted volunteers in Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, China, and beyond to assess available resources.

Items assembled to ship included folding beds, blankets, mosquito nets, tents, and dry food—basic necessities for those sleeping outdoors. The goal was to offer protection from the elements, insulation from the ground, and relief from insect bites. But as shipments were readied, one major obstacle remained: Would the Myanmar government allow foreign humanitarian aid into the country? And if so, would local Tzu Chi volunteers be permitted to distribute it directly to survivors?

In Mandalay, many people had taken to sleeping in the streets or open fields. Jiang noted that mosquito bites were a serious issue at night. Most people had no tents—just a blanket on the bare ground. To make a bad situation worse, weather forecasts warned of an approaching cyclone. On the evening of April 5, heavy rain began falling. Jiang worried aloud, "It's raining so hard. How will the survivors cope?"

Though Tzu Chi had prepared supplies in several countries, it was still unclear as of April 3 whether aid from Tzu Chi could be brought into Myanmar. For example, Malaysian volunteer Teoh Paik Lim (張濟玄) had learned on the day of the quake that the Malaysian government was planning to send aid into Myanmar. Recognizing the urgent need for as much assistance as possible, he alerted Tzu Chi Malaysia and began mobilizing support. However, since the shipment would go by military aircraft and government-to-government negotiations were required, no departure date had been confirmed.

At the same time, Tzu Chi was pursuing a parallel track to send aid as a non-governmental organization (NGO), without relying on government channels. But for now, they could only wait, hoping local volunteers in Myanmar would quickly succeed in securing the necessary permission to bring aid into the country.

Volunteers offer support at a stadium in Mandalay. In the aftermath of the quake, over 200 households set up camp on trucks there.

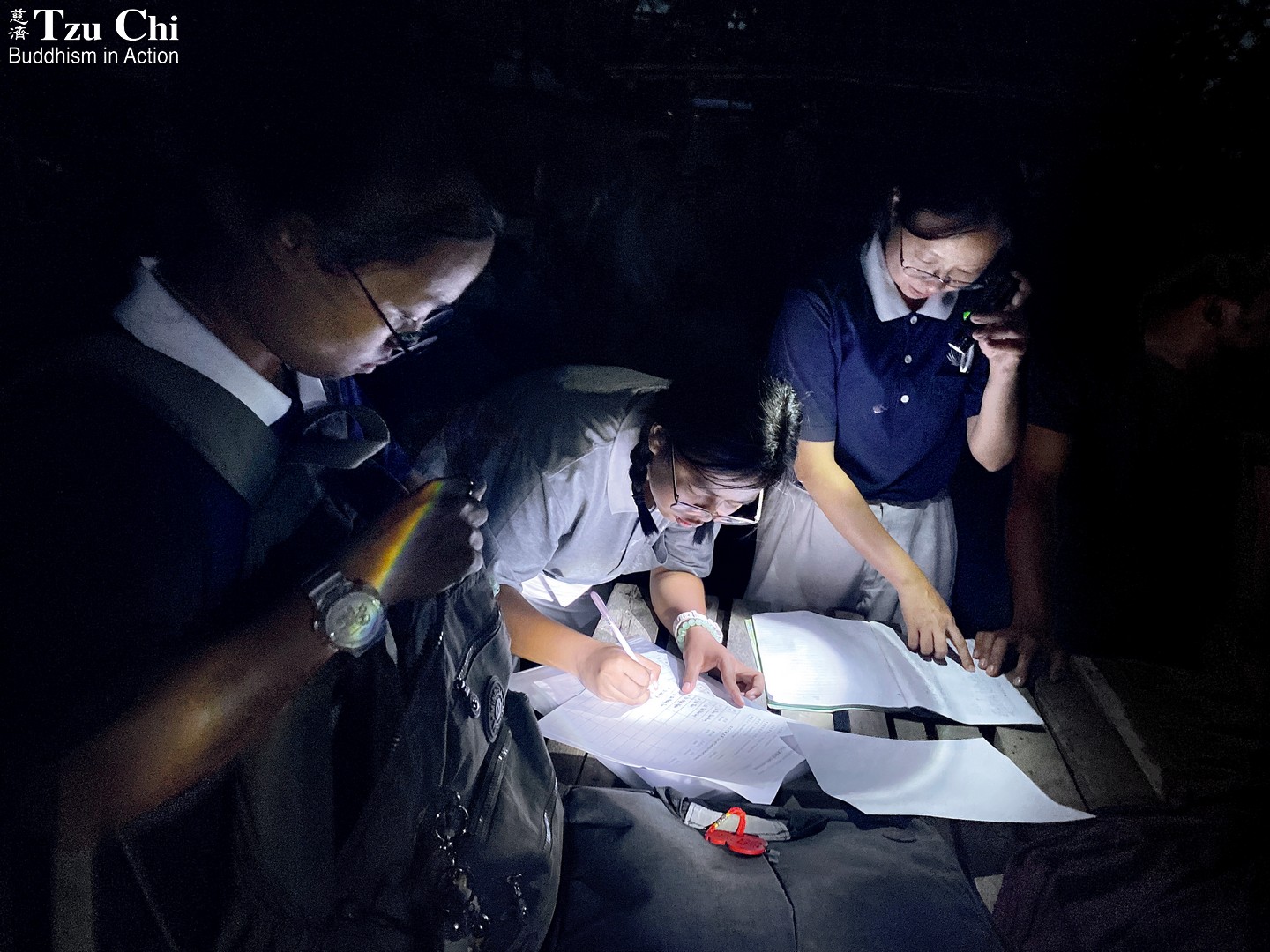

Most of the monks' quarters at Maha Gandar Yone Monastery were damaged. Volunteers are pictured here working late into the night, planning to set up waterproof tents in the open area behind the monastery to prepare for the upcoming rainy season. (Khant Khant Maung)

Assessing the damage

On April 1, Daw Thida Khin returned to Yangon from Taiwan. The following day, she and two fellow volunteers, Aye Nandar Aung (郭寶鈺) and Wen Si Lang (溫斯朗), each led a team to Mandalay to assess the damage. A trip that normally took eight hours stretched to 13 due to damaged roads.

Their primary mission was to gain a clear understanding of conditions across affected communities. Their visits included hospitals, temples, monasteries, and other key sites. In Myanmar, temples and monasteries are not only religious centers but also serve as crucial shelters and food distribution hubs during crises. Many had sustained damage in the quake and needed aid themselves. Dharma Master Cheng Yen reminded volunteers to include such spiritual sites, as well as orphanages and nursing homes, in their relief efforts.

Although international Tzu Chi supplies had not yet arrived, local volunteers had already made meaningful progress. Within three days of the disaster, large quantities of relief goods had been distributed. Though not a Tzu Chi volunteer before the quake, Jiang Rong Hua helped deliver some 4,000 portions of bread, water, and sports drinks to hard-hit communities and hospitals. Volunteer Lin Zhi Min (林治民) and his family also provided 250 boxed meals for frontline responders.

Lin and U Kyaw Khin (林銘慶), a local businessman who had supported Tzu Chi since Cyclone Nargis in 2008, also played a key role in coordinating the import of supplies into Myanmar.

Tzu Chi Indonesia had planned to deliver five generators and over a thousand sets of daily essentials via Indonesian military transport on April 3. However, the shipment was ultimately put on hold. It was a disappointment for the volunteers who had worked hard to prepare the aid, especially because it meant the supplies might not reach those in need.

Meanwhile, Tzu Chi Malaysia had been awaiting confirmation to send their shipment. Initially scheduled to go out on April 23, the date was first moved up to April 12 and finally finalized for April 7. But the go-ahead didn't come until April 3—leaving just three days to gather supplies, arrange transport, and load the aircraft. The compressed timeline placed the team under considerable pressure.

On April 4, folding beds from the Tzu Chi Yangon office arrived in Mandalay, with priority given to rescue teams and hospitals. (Nay Thura)

The first shipment

Twenty-one volunteers gathered at Low Ping Kun's (劉炳坤) rubber processing factory in Kedah to prepare more than 500 folding beds for delivery. The volunteers stacked the beds into tall piles and secured them with industrial plastic wrap. When 20 Myanmar employees at the factory learned that the aid was destined for their homeland, they all chose to stay after work to help.

Once the beds and other supplies were ready, a team transported them to a Royal Malaysian Air Force base and worked with the Red Cross and other organizations to arrange cargo space. In the end, only 80 of the 520 folding beds were approved to be loaded onto the military aircraft. Yet volunteer Teoh Paik Lim remained optimistic, recalling, "We were fortunate to get all 690 blankets on board."

Upon arrival at Naypyidaw, Myanmar's capital, the supplies cleared customs with the help of Tzu Chi Malaysia CEO Koay Chiew Poh (郭濟緣), volunteer U Kyaw Khin, and Red Cross officials. The items were then transferred to Tzu Chi Myanmar for direct distribution.

Meanwhile, U Kyaw Khin and Lin Zhi Min actively approached various government agencies to seek permits allowing Tzu Chi to ship relief supplies to Myanmar as an NGO. Preliminary approval was granted by the Foreign Ministry on April 5. Based on local assessments in quake-affected areas, the list of relief items was adjusted to better match actual needs. In addition to folding beds, mosquito nets, and dry food, they included sleeping bags, solar lamps, and medical protective gear. Tzu Chi staff member Liang Si-yu explained the main focus on non-food necessities: "We're sourcing food locally as much as possible. Besides, our volunteers have reported that many other NGOs are also distributing food."

On the morning of April 7, Malaysian volunteers Teoh Paik Lim (third from right) and Lee Chong Hoo (second from right) accompanied the Royal Malaysian Air Force in delivering folding beds and blankets from Malaysia to Myanmar. (Courtesy of Teoh Paik Lim)

Overwhelming loss

The death toll immediately following the earthquake was reported as only 50 persons. By April 1, that number had risen to over 2,000; by mid-April, it had exceeded 3,600. "Many buildings couldn't be cleared in time, and countless people remain buried under the rubble," said Daw Thida Khin during a video conference with Tzu Chi's headquarters in Hualien, Taiwan.

Despite the official reports, the true number of casualties remained unknown, deepening the collective grief in the country. In Mandalay, the Great Wall Hotel had collapsed. Ma La Min Thu survived the disaster, but her sister and brother-in-law remained trapped beneath the debris. Her mother, Yi Naing, had rushed from northern Myanmar on March 30 and had been staying at a nearby temple, waiting anxiously. When a Tzu Chi team met them on April 8, Ma La Min Thu wept openly. Though she had escaped with her life, the anguish of not knowing her loved ones' fate was unbearable. Volunteers gave the family condolence money—a small gesture of care amid overwhelming loss.

Stories like theirs were tragically common. Volunteers assessed needs at hospitals, religious centers, orphanages, and shelters. Whenever possible, supplies were sourced locally and delivered swiftly. These included dry food, drinking water, toiletries, and feminine hygiene products. The latter were important for the comfort and dignity of women and girls.

Tzu Chi's folding beds also made a real difference, be it for survivors, patients, or exhausted medical workers. Most people were sleeping on mats outdoors, but with daytime temperatures nearing 40°C (104°F), the intense heat radiating from the ground at night made rest nearly impossible. Elevated and providing air flow, the beds provided much-needed relief, allowing people to truly rest.

With the rainy season approaching, volunteers launched a cash-for-work program, hiring local residents to help build rain shelters using tarps, bamboo poles, and straw mats provided by Tzu Chi. One participant shared that his wife had sustained head and hand injuries during the quake. With the money he earned from the program, he was finally able to take her to see a doctor.

During their first week in the disaster zone, volunteers visited 20 villages to better understand local needs. For families who had lost loved ones, condolence money was provided. During their second week, from April 13 to 18, they returned to those same villages to carry out distributions.

Approximately 2,000 homes were damaged in Tada-U Township, near the quake's epicenter. Visiting volunteers found almost every household there working to clear away rubble. On April 14, aid was distributed to families who had lost their homes or suffered fatalities or serious injuries. Each family received emergency cash, rice, and cooking oil. Smiles appeared on recipients' faces when they received the aid, as if a heavy burden had been lifted.

Tada-U is rich in Buddhist history, known for its historic relics. During her visit assessing the damage there, volunteer Aye Nandar Aung was deeply saddened to see that all the temples along her route had collapsed. The earthquake had not only destroyed countless homes and lives but had also erased centuries of heritage and culture.

The loss of temples and pagodas dealt a heavy blow—not just spiritually and culturally, but economically as well. These sites were vital to the local tourism industry. Now, with livelihoods disrupted, recovery has become even more daunting.

For more than a decade, Malaysian volunteer Cecelia Ong has traveled to Myanmar to assist after major disasters. Her many visits have deepened her admiration for the local people. "They are not greedy," she said. "When they receive cash aid, they always say, ‘Our lives weren't bad before. If possible, we'd rather not need help.'" With emotion, she added, "They are such kind people, yet they have endured so much."

As Tzu Chi's relief distributions continued, the first chartered flight arranged by Tzu Chi Malaysia through the United Nations Humanitarian Response Depot arrived in Mandalay in mid-April, carrying 1,349 folding beds. A second flight followed soon after. Meanwhile, Tzu Chi volunteers in about 20 countries and regions had launched fundraising campaigns to support the foundation's mission in Myanmar.

On April 18, the disaster assessment teams completed their emergency distributions and began to return to Yangon. With a better understanding of the overall situation, volunteers began planning for mid- and long-term support. But the future remains uncertain. Myanmar has long struggled with internal conflict, and while the earthquake prompted a temporary ceasefire between the military government and resistance forces, it lasted only from April 2 to April 30.

Whether humanitarian organizations like Tzu Chi will be allowed to continue their work after the ceasefire remains unclear, let alone the restoration of the country's damaged cultural landmarks. For now, volunteers are doing all they can, hoping to bring more comfort and hope to those who have already endured so much.

People sit on a folding bed provided by Tzu Chi in the temporary inpatient area of Mandalay Orthopaedic Hospital. The concept for this bed was inspired by the 2010 Pakistan flood relief efforts, when a newborn was found lying on the cold, damp earth. Designed with a hollow structure that promotes breathability, the bed is elevated 30 centimeters off the ground to remain dry in damp environments. It can be unfolded by hand without the need for assembly tools and folded for convenient transport. (Nay Thura)

Local residents construct temporary shelters at Maha Gandar Yone Monastery, where monks were forced to sleep outdoors after the earthquake. They were participants in a cash-for-work program launched by Tzu Chi to build shelters at affected sites. Initial estimates suggested that more than 3,000 religious buildings were damaged in the tremor.

Contact Us | Plan a Visit | Donate

8 Lide Road, Beitou 11259, Taipei, Taiwan

886-2-2898-9999

005741@daaitv.com

©Tzu Chi Culture and Communication Foundation

All rights reserved.