Mailbox 200: The Kyrgyzstan's Uranium Legacy

Text and photos by Riccardo Bononi/Parallelozero

Abridged by Syharn Shen (沈思含)

Mailbox 200: The Kyrgyzstan's Uranium Legacy

Text and photos by Riccardo Bononi/Parallelozero

Abridged by Syharn Shen (沈思含)

In Mayluu Suu, Kyrgyzstan—formerly known as "Mailbox 200"—the Soviet nuclear program's legacy lingers. This once secret uranium mining hub remains one of the most radioactive places on Earth, still posing a threat to local residents and millions downstream.

The entrance to the city of Mayluu Suu in the region of Jalal-Abad in Kyrgyzstan, is located 1.4 km from the nearest radioactive waste dump. Home to 25,000 people, the city's name "Mayluu Suu" means "oily water," reflecting the petroleum and rare metal residues found in its river.

Malyuu Suu, known during the Soviet era only as "Mailbox 200," was recently named one of the most radioactive places on Earth, alongside Fukushima and Chernobyl. From 1946 to 1968, over 10,000 tons of uranium were extracted from its mines by prisoners, including Soviet dissidents and German soldiers, unaware of the radioactive dangers. The term "uranium" was forbidden in the mines, and radioactive minerals were transported without any protection, often on the backs of donkeys. To the outside world, the mine produced only coal and other common materials.

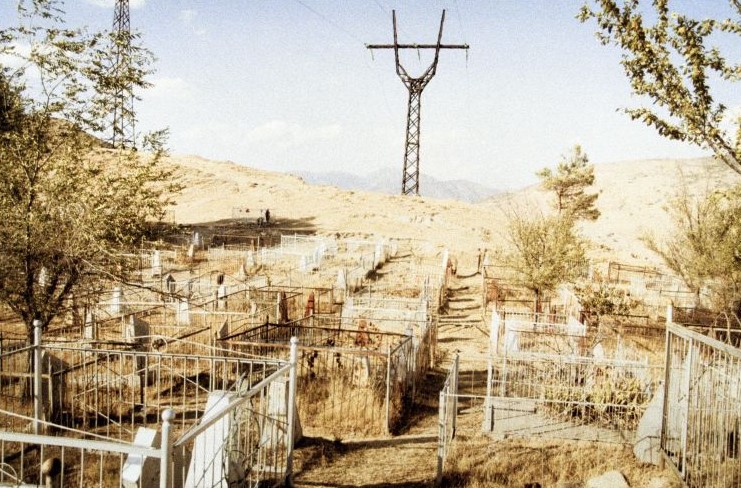

On the hills of Mayluu Suu, 1 km from the nearest radioactive waste dump, lies one of the largest Orthodox cemeteries in Kyrgyzstan, where Russian miners who extracted uranium between 1946 and 1968 are buried.

Today, traces of those prisoners' lives remain in the Orthodox graves scattered across a hill near the city. From this hill, one can see both the abandoned uranium mines and the lives of the town's 25,000 inhabitants, many of whom are descendants of the miners. This land provided the resources for the first Soviet atomic bomb and built the foundation of the Soviet nuclear arsenal, a threat still echoing in the Russian Federation today.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan emerged suddenly as an independent state, with no gradual transition. More than 2 million cubic meters of radioactive waste were abandoned, buried in the mountains surrounding Malyuu Suu, some of it just 200 meters from homes and fields. Containment tanks now hold much of this waste, but landslides and floods pose a constant risk of exposure. A 1958 landslide destroyed several tanks, releasing 600,000 cubic meters of radioactive waste into the river and spreading contamination through Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Environmental experts estimate it will take more than two centuries for radioactivity to return to safe levels.

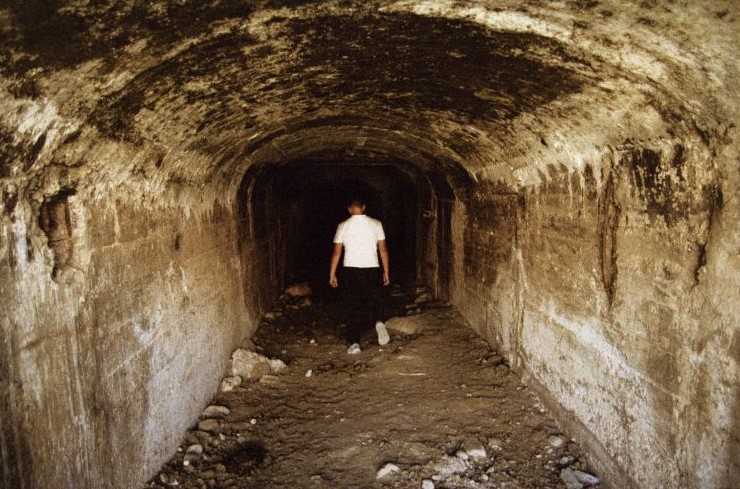

Inside an abandoned uranium mine in Mayluu Suu, just 40 meters from the nearest radioactive waste dump, this site once supplied uranium for the Soviet atomic bomb project. Today, it is used by shepherds as makeshift stables.

Even today, the former village "Mailbox 200" records dangerously high levels of radiation, with peaks reaching 5000 nSv/h near the worst storage sites, far surpassing Chernobyl in some cases. The drinking and agricultural water for Malyuu Suu's residents come directly from the contaminated river. Despite this, life in the city continues—children go to school, parents work, and residents swim in the river. Yet, the WHO reports the highest rates of cancer, thyroid disease, Down syndrome, and fetal pathologies in the entire country are found here.

The Mayluu Suu River, 1 km from the nearest radioactive waste dump, flows into the Naryn River, which continues through the Fergana Valley, one of Central Asia's most populated regions. This contaminated water, used for drinking, agriculture, and livestock farming, threatens the health of millions in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan.

Though efforts by NATO and other countries have aimed at mitigating the contamination, Russia has refused to take part in the cleanup, denying any responsibility for the radiation problems. Some locals even support Russia's stance, hoping instead to promote tourism and reverse the city's depopulation. Meanwhile, Russia continues to show interest in Kyrgyzstan's uranium stocks, fostering nuclear research ties with the country.

This legacy resurfaced in October 2023, when Russian President Vladimir Putin, accompanied by Rosatom representatives, visited Kyrgyzstan to meet with President Sadyr Japarov. Soon after, Putin revoked Russia's ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty, paving the way for new nuclear testing. Kyrgyzstan's uranium, buried beneath Malyuu Suu, remains at the heart of global nuclear tensions, and the scars of the Cold War are far from healed.

In front of the Kyrgyz Academy of Sciences in Bishkek stands the "Peaceful Atom" monument, a reminder of the country's atomic legacy and the unresolved issues surrounding uranium mining.

Contact Us | Plan a Visit | Donate

8 Lide Road, Beitou 11259, Taipei, Taiwan

886-2-2898-9999

005741@daaitv.com

©Tzu Chi Culture and Communication Foundation

All rights reserved.