Coral Restoration in Taiwan

By Chiachen Wu (吳佳珍)

Photos by Chang Hao-jan (張皓然)

Abridged and translated by Chang Yu Ming (張佑民)

Coral Restoration in Taiwan

By Chiachen Wu (吳佳珍)

Photos by Chang Hao-jan (張皓然)

Abridged and translated by

Chang Yu Ming (張佑民)

This coral near a nuclear power plant in southern Taiwan is bleaching because of warmer waters. However, research has shown that the corals there are slowly adapting and adjusting to the warmer temperature. (Photo by Hsu Chia-min)

"It's so soft!" "It's sticking to my hand!" On the third weekend of July, visitors at a marine life restoration center in New Taipei City, Taiwan, came into contact with living corals for the first time.

"Corals' tentacles are soft, and are used to capture critters for food. However, their bones are very hard," explained Dr. Shikina Shinya (識名信也), associate professor at Institute of Marine Environment and Ecology, National Taiwan Ocean University. After a brief introduction to corals and the dangers they face, Dr. Shikina and his team started teaching the visitors how to plant corals.

It is actually very simple, so even children can do it. Cut the coral to five centimeter in length, glue it onto a base, and put it in a nursery pond that simulates the ocean. Once the corals have grown, they are then outplanted to an outdoor pool and will eventually go back into the ocean.

For Acropora corals, their survival rate in the nursery pond is up to 90% and they can grow very quickly, at around 10 centimeters a year. "However, Acropora is very sensitive to environmental changes, so they bleach easily," said Dr. Shikina.

Dr Shikina and his team nurture corals in indoor nurseries first before moving them to outdoor pools. (Photos by Huang Shi-ze)

What are Corals?

Corals come in many shapes and sizes. They can look like twigs or stones, and because they are attached to the ground, people often mistake them to be plants or rocks. Coral is actually an animal belonging to the same category as sea anemone and jellyfish, called Cnidaria. Corals can also secrete calcium carbonate to form skeleton.

The smallest unit of a coral is called a 'polyp', and its size can range from a diameter of one millimeter to more than ten centimeters. When we say we see a 'coral', it is actually a colony made up of many polyps. These colonies often adapt to their living environment, so a coral of the same species can look very different when living in a different environment.

Other than the energy from algae, corals also use their tentacles to capture planktons for food.

In the coral family, not every coral can build reefs. The main contributors to the reefs are the stony corals, also known as reef-building corals. These reef-building corals have algae living inside them, so they can be said to be a combination of animal tissues and plant tissues.

The algae create energy for the corals through photosynthesis and feed on the waste produced by the corals. The algae provide more than 80% of the energy needed by the corals.

Moreover, corals' colors come not only from their own pigments, but from the algae as well. When environmental conditions deteriorate, the corals will expel the algae; and since coral tissues are transparent, only their white skeleton can be seen. This is known as 'coral bleaching'. Bleaching does not mean immediate death for the corals, it is more of like flu to them. The corals can recover if the conditions improve, but if not, they can die in a few days.

The Ocean's Rainforest

What do the coral have to do with the habitat, and us humans? Why do we need to restore them? First, we need to know what the purpose of corals is.

To the ocean, coral reef is like its rainforest. The reefs provide shelters for marine life, a place to hunt for food or to hide from predators. Although coral reefs only take up about 0.1% of ocean's surface area, they house up to 50 thousand different types of life under their 'roof'. They constitute one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth.

The white skeleton proves that this coral branch is still alive and growing.

Humans also benefit from coral reefs, which are natural breakwaters. These reefs can absorb 97% of wave energy and reduce 84% of wave height, protecting coastal communities. They also have significant economic value, measuring up to 4 thousand billion U.S. dollars per year in areas such as fisheries, tourism, and medicinal research. More than 500 million people rely on coral reefs for their livelihood. Even without any personal contact with the reefs, all of us definitely benefit from them, directly or indirectly.

However, reef-building corals (such as Acropora) have high demands for their living environments. First, the water temperature has to be between 18 to 30 degrees Celsius, no higher or lower. They also need ample sunlight as they have algae living in their tissues that photosynthesize to provide energy for them. Thirdly, the water has to be clear, without too much sediments or planktons. When their living environment is polluted, they can die easily if the pollutants are not removed promptly.

Under Serious Threat

Dr. Allen Chen (陳昭倫), a researcher from the Academia Sinica's Biodiversity Research Center, told us that the corals in the world are facing four main threats: overfishing, destruction of habitats, marine pollution, and climate change.

According to a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the average Earth temperature has already risen one degree Celsius since the industrial revolution. Once we reach two degrees Celsius, 99% of the coral reefs will be gone by 2050. However, if we can achieve zero carbon emissions before that, the temperature rise can be kept at 1.5 degrees Celsius. "The difference of 0.5 degrees can save at least 10% to 30% of coral reefs," sighed Dr. Chen.

A housewife with a heart for environmental conservation, Elaine accidentally found abundant life in abandoned abalone farms, and decided to grow corals in them. (Photo by Huang Shi-ze)

Growing Corals in Abalone Farms

Elaine Chen (陳映伶), secretary general of a environmental conservation association in Taiwan, has been growing corals in abandoned abalone farms in a bid to restore the beautiful seabed. "I didn't expect this project to grow so much when we started five years ago. We managed to receive funding from the Ocean Conservation Administration this year so we can finally move the corals from the farms to the coasts!" said Elaine happily.

Elaine and her team use corals discarded by abalone farmers as seedlings, and just let the corals grow freely after securing them inside the nursery pond. There are now various types of corals and numerous fishes, shrimps, crabs, etc. swimming in the pond.

Whilst doing the interview, I also gave planting corals a go. Each coral branch was tied onto a rope with a 30 cm space in between. The string of corals was then quickly lowered and secured in the pond so the corals were not out of the water for too long.

After five years of growing, some corals already grew to a diameter of 50 cm. Elaine hoped that she can see the corals reproduce naturally one day.

Corals can reproduce sexually and asexually. For sexual reproduction, the corals release sperms and eggs that will form into larvae, and will grow and establish their own colony. For asexual reproduction, one of the methods is fragmentation, where corals break away from the colony, reattach somewhere else, and form a new colony. Most of the man-made restorations of corals make use of this characteristic.

Elaine and her team hang coral branches on ropes and nurture them in nursery ponds. (Photos by Huang Shi-ze)

However, asexual reproduction can only create mere copies of the same DNA. Even though the coral colony can expand quickly, once the environment condition changes, the whole colony can be wiped out in a second. Sexual reproduction can diversify the genes and produce stronger, fitter corals. Hence, Dr. Shikina believes that the best way to restore corals is to employ both reproductive methods: Using asexual reproduction first to increase the number of corals. After collecting sperms and eggs from different genes, nurture the fertilized eggs to create a mix in a single type of coral. The drawback is that sexual reproduction needs to wait for the larvae to mature, which usually takes at least five years.

"There's still a long way to go," said Dr. Shikina. There are more than a thousand species of reef-building corals, but we only know how to restore around a hundred of them for now. "There is still so much that we don't know about corals. If we can learn more about them, maybe one day we can find more ways to save them."

Restoring Coral Reefs at Penghu

Many places in the world are restoring coral reefs, such as the Caribbean in the United States, Indonesia, Australia, and also Okinawa in Japan. Taiwan joined in on the efforts in the 1990s, when coral research began at the National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, and at National Sun Yat-sen University. Dr. Chen was part of the research team at the island of Penghu more than ten years ago.

Shean Yi-yueh collects broken coral branches and gets ready to replant them.

Many government agencies and NGOs are growing corals in Penghu. Dr. Chen explained that Penghu has excellent terrains that can protect the corals, and already has many old coral habitats. If the wastewater and pollutants can be removed, there is a good chance that the restoration of coral colonies can succeed.

At one of the beaches in Penghu, we dived underwater to visit the 4000 square meter of coral restoration ground with our guide, Shean Yi-yueh (冼宜樂), a diver from Penghu Marine Biology Research Center.

In the silence, we could only hear the slow hum of the currents. The water was a little muddy, but we were told that today's water quality was considered good. After a short swim, we were greeted by a field of Acropora formosa, stretching openly on the seafloor. Colorful butterflyfishes could be seen hiding in the corals, sand snappers and longfin groupers swimming around freely, parrotfishes and sea urchins feasting on the algae on the corals.

Similar to land gardening, corals can be planted as well.

Shean then nailed steel bars on the seafloor and tied broken branches of corals on them. He made sure the branches were a few inches off the ground so they would not be buried by the sand. This method of planting corals is somewhat similar to the cutting propagation of plants, and allows the corals to grow freely.

For coral restoration, Shean is all about natural growth. He does not interfere with the corals too much and simply let nature do its thing. On the second year of restoration, the corals were almost fully covered by seaweeds. Shean almost wanted to intervene, but ultimately decided not to help the corals remove their competitors. Luckily, the number of seaweeds slowly dwindled a few months later.

He was even happy for the corals if there was a hurricane. He explained that man-made restoration could only grow corals individually. But after the hurricane, the broken branches that fall onto the seafloor can grow to strengthen the base and also form a natural-looking coral colony.

Allies in Marine Life Conservation

"They are using steel bars to grow corals? That's what we are going to try next! We were using disposable chopsticks or metal chopsticks," said Chen Yi-jun (陳宜君), a supervisor of Penghu Ocean Citizen Foundation. The foundation started planting corals since 2017, and out of 600 branches every year, about half of them survived.

Penghu Ocean Citizen Foundation often organizes classes to bring people closer to the world of corals. |

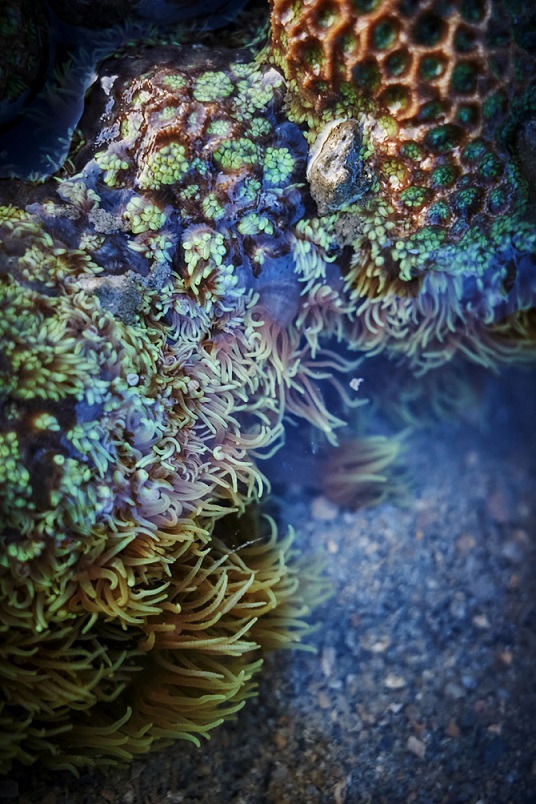

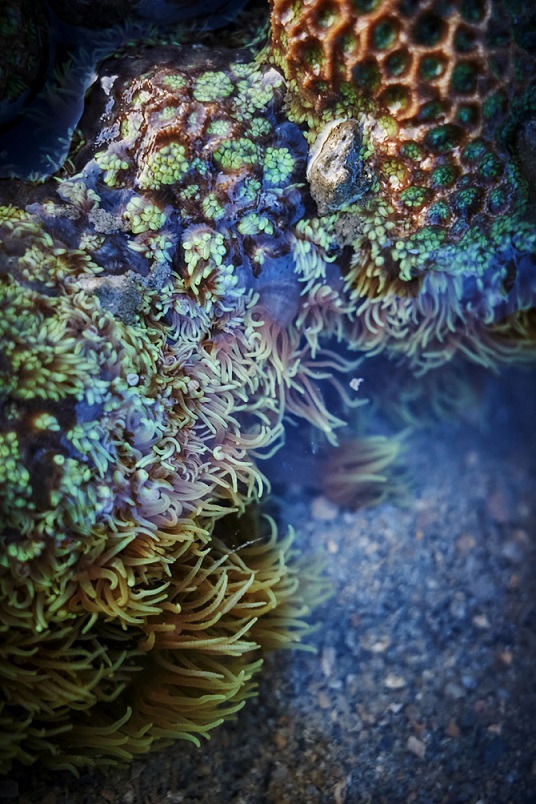

Various types of corals can be found in Penghu's intertidal zones. |

"As an NGO, it's important for us to find allies," Chen commented. Not just for funding, but to also expand influence and raise awareness. The foundation is currently promoting environmental awareness through local bed and breakfasts and also diving instructors.

"They attend to so many tourists every day, every reminder on environmental protection will help!" said Chen. Last year, the foundation collaborated with Taiwan Environmental Information Association and four dive shops to do a thorough record of the coral reefs around Penghu. Chen believed that after learning more about the corals, these diving instructors can then share their experiences and knowledge with their customers.

"People asked me why I grow corals." Chen replied, "If we do nothing, that's not better for the environment either." Even though we are unable to restore coral reefs to their original state, we can still grow as much corals as we can, nurture their genetic diversity, and guide the environment towards natural recovery.

It is not about what we do, but our commitment to keep trying.

Coral reefs can be a feeding ground, a hunting ground, or a shelter to many different marine life forms.

This coral near a nuclear power plant in southern Taiwan is bleaching because of warmer waters. However, research has shown that the corals there are slowly adapting and adjusting to the warmer temperature. (Photo by Hsu Chia-min)

"It's so soft!" "It's sticking to my hand!" On the third weekend of July, visitors at a marine life restoration center in New Taipei City, Taiwan, came into contact with living corals for the first time.

"Corals' tentacles are soft, and are used to capture critters for food. However, their bones are very hard," explained Dr. Shikina Shinya (識名信也), associate professor at Institute of Marine Environment and Ecology, National Taiwan Ocean University. After a brief introduction to corals and the dangers they face, Dr. Shikina and his team started teaching the visitors how to plant corals.

It is actually very simple, so even children can do it. Cut the coral to five centimeter in length, glue it onto a base, and put it in a nursery pond that simulates the ocean. Once the corals have grown, they are then outplanted to an outdoor pool and will eventually go back into the ocean.

For Acropora corals, their survival rate in the nursery pond is up to 90% and they can grow very quickly, at around 10 centimeters a year. "However, Acropora is very sensitive to environmental changes, so they bleach easily," said Dr. Shikina.

Dr Shikina and his team nurture corals in indoor nurseries first before moving them to outdoor pools. (Photos by Huang Shi-ze)

What are Corals?

Corals come in many shapes and sizes. They can look like twigs or stones, and because they are attached to the ground, people often mistake them to be plants or rocks. Coral is actually an animal belonging to the same category as sea anemone and jellyfish, called Cnidaria. Corals can also secrete calcium carbonate to form skeleton.

The smallest unit of a coral is called a 'polyp', and its size can range from a diameter of one millimeter to more than ten centimeters. When we say we see a 'coral', it is actually a colony made up of many polyps. These colonies often adapt to their living environment, so a coral of the same species can look very different when living in a different environment.

Other than the energy from algae, corals also use their tentacles to capture planktons for food.

In the coral family, not every coral can build reefs. The main contributors to the reefs are the stony corals, also known as reef-building corals. These reef-building corals have algae living inside them, so they can be said to be a combination of animal tissues and plant tissues.

The algae create energy for the corals through photosynthesis and feed on the waste produced by the corals. The algae provide more than 80% of the energy needed by the corals.

Moreover, corals' colors come not only from their own pigments, but from the algae as well. When environmental conditions deteriorate, the corals will expel the algae; and since coral tissues are transparent, only their white skeleton can be seen. This is known as 'coral bleaching'. Bleaching does not mean immediate death for the corals, it is more of like flu to them. The corals can recover if the conditions improve, but if not, they can die in a few days.

The Ocean's Rainforest

What do the coral have to do with the habitat, and us humans? Why do we need to restore them? First, we need to know what the purpose of corals is.

To the ocean, coral reef is like its rainforest. The reefs provide shelters for marine life, a place to hunt for food or to hide from predators. Although coral reefs only take up about 0.1% of ocean's surface area, they house up to 50 thousand different types of life under their 'roof'. They constitute one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth.

The white skeleton proves that this coral branch is still alive and growing.

Humans also benefit from coral reefs, which are natural breakwaters. These reefs can absorb 97% of wave energy and reduce 84% of wave height, protecting coastal communities. They also have significant economic value, measuring up to 4 thousand billion U.S. dollars per year in areas such as fisheries, tourism, and medicinal research. More than 500 million people rely on coral reefs for their livelihood. Even without any personal contact with the reefs, all of us definitely benefit from them, directly or indirectly.

However, reef-building corals (such as Acropora) have high demands for their living environments. First, the water temperature has to be between 18 to 30 degrees Celsius, no higher or lower. They also need ample sunlight as they have algae living in their tissues that photosynthesize to provide energy for them. Thirdly, the water has to be clear, without too much sediments or planktons. When their living environment is polluted, they can die easily if the pollutants are not removed promptly.

Under Serious Threat

Dr. Allen Chen (陳昭倫), a researcher from the Academia Sinica's Biodiversity Research Center, told us that the corals in the world are facing four main threats: overfishing, destruction of habitats, marine pollution, and climate change.

According to a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the average Earth temperature has already risen one degree Celsius since the industrial revolution. Once we reach two degrees Celsius, 99% of the coral reefs will be gone by 2050. However, if we can achieve zero carbon emissions before that, the temperature rise can be kept at 1.5 degrees Celsius. "The difference of 0.5 degrees can save at least 10% to 30% of coral reefs," sighed Dr. Chen.

A housewife with a heart for environmental conservation, Elaine accidentally found abundant life in abandoned abalone farms, and decided to grow corals in them. (Photo by Huang Shi-ze)

Growing Corals in Abalone Farms

Elaine Chen (陳映伶), secretary general of a environmental conservation association in Taiwan, has been growing corals in abandoned abalone farms in a bid to restore the beautiful seabed. "I didn't expect this project to grow so much when we started five years ago. We managed to receive funding from the Ocean Conservation Administration this year so we can finally move the corals from the farms to the coasts!" said Elaine happily.

Elaine and her team use corals discarded by abalone farmers as seedlings, and just let the corals grow freely after securing them inside the nursery pond. There are now various types of corals and numerous fishes, shrimps, crabs, etc. swimming in the pond.

Whilst doing the interview, I also gave planting corals a go. Each coral branch was tied onto a rope with a 30 cm space in between. The string of corals was then quickly lowered and secured in the pond so the corals were not out of the water for too long.

After five years of growing, some corals already grew to a diameter of 50 cm. Elaine hoped that she can see the corals reproduce naturally one day.

Corals can reproduce sexually and asexually. For sexual reproduction, the corals release sperms and eggs that will form into larvae, and will grow and establish their own colony. For asexual reproduction, one of the methods is fragmentation, where corals break away from the colony, reattach somewhere else, and form a new colony. Most of the man-made restorations of corals make use of this characteristic.

Elaine and her team hang coral branches on ropes and nurture them in nursery ponds. (Photos by Huang Shi-ze)

However, asexual reproduction can only create mere copies of the same DNA. Even though the coral colony can expand quickly, once the environment condition changes, the whole colony can be wiped out in a second. Sexual reproduction can diversify the genes and produce stronger, fitter corals. Hence, Dr. Shikina believes that the best way to restore corals is to employ both reproductive methods: Using asexual reproduction first to increase the number of corals. After collecting sperms and eggs from different genes, nurture the fertilized eggs to create a mix in a single type of coral. The drawback is that sexual reproduction needs to wait for the larvae to mature, which usually takes at least five years.

"There's still a long way to go," said Dr. Shikina. There are more than a thousand species of reef-building corals, but we only know how to restore around a hundred of them for now. "There is still so much that we don't know about corals. If we can learn more about them, maybe one day we can find more ways to save them."

Restoring Coral Reefs at Penghu

Many places in the world are restoring coral reefs, such as the Caribbean in the United States, Indonesia, Australia, and also Okinawa in Japan. Taiwan joined in on the efforts in the 1990s, when coral research began at the National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, and at National Sun Yat-sen University. Dr. Chen was part of the research team at the island of Penghu more than ten years ago.

Shean Yi-yueh collects broken coral branches and gets ready to replant them.

Many government agencies and NGOs are growing corals in Penghu. Dr. Chen explained that Penghu has excellent terrains that can protect the corals, and already has many old coral habitats. If the wastewater and pollutants can be removed, there is a good chance that the restoration of coral colonies can succeed.

At one of the beaches in Penghu, we dived underwater to visit the 4000 square meter of coral restoration ground with our guide, Shean Yi-yueh (冼宜樂), a diver from Penghu Marine Biology Research Center.

In the silence, we could only hear the slow hum of the currents. The water was a little muddy, but we were told that today's water quality was considered good. After a short swim, we were greeted by a field of Acropora formosa, stretching openly on the seafloor. Colorful butterflyfishes could be seen hiding in the corals, sand snappers and longfin groupers swimming around freely, parrotfishes and sea urchins feasting on the algae on the corals.

Similar to land gardening, corals can be planted as well.

Shean then nailed steel bars on the seafloor and tied broken branches of corals on them. He made sure the branches were a few inches off the ground so they would not be buried by the sand. This method of planting corals is somewhat similar to the cutting propagation of plants, and allows the corals to grow freely.

For coral restoration, Shean is all about natural growth. He does not interfere with the corals too much and simply let nature do its thing. On the second year of restoration, the corals were almost fully covered by seaweeds. Shean almost wanted to intervene, but ultimately decided not to help the corals remove their competitors. Luckily, the number of seaweeds slowly dwindled a few months later.

He was even happy for the corals if there was a hurricane. He explained that man-made restoration could only grow corals individually. But after the hurricane, the broken branches that fall onto the seafloor can grow to strengthen the base and also form a natural-looking coral colony.

Allies in Marine Life Conservation

"They are using steel bars to grow corals? That's what we are going to try next! We were using disposable chopsticks or metal chopsticks," said Chen Yi-jun (陳宜君), a supervisor of Penghu Ocean Citizen Foundation. The foundation started planting corals since 2017, and out of 600 branches every year, about half of them survived.

Penghu Ocean Citizen Foundation often organizes classes to bring people closer to the world of corals.

"As an NGO, it's important for us to find allies," Chen commented. Not just for funding, but to also expand influence and raise awareness. The foundation is currently promoting environmental awareness through local bed and breakfasts and also diving instructors.

Various types of corals can be found in Penghu's intertidal zones.

"They attend to so many tourists every day, every reminder on environmental protection will help!" said Chen. Last year, the foundation collaborated with Taiwan Environmental Information Association and four dive shops to do a thorough record of the coral reefs around Penghu. Chen believed that after learning more about the corals, these diving instructors can then share their experiences and knowledge with their customers.

"People asked me why I grow corals." Chen replied, "If we do nothing, that's not better for the environment either." Even though we are unable to restore coral reefs to their original state, we can still grow as much corals as we can, nurture their genetic diversity, and guide the environment towards natural recovery.

It is not about what we do, but our commitment to keep trying.

Coral reefs can be a feeding ground, a hunting ground, or a shelter to many different marine life forms.

Contact Us | Plan a Visit | Donate

8 Lide Road, Beitou 11259, Taipei, Taiwan

886-2-2898-9999

005741@daaitv.com

©Tzu Chi Culture and Communication Foundation

All rights reserved.