Kamikatsu: Japan's Zero-Waste Town

By Chiachen Wu (吳佳珍)

Photos by Alberto Buzzola

Abridged and translated by George Chen (陳纘強)

Kamikatsu: Japan's Zero-Waste Town

By Chiachen Wu (吳佳珍)

Photos by Alberto Buzzola

Abridged and translated

by George Chen (陳纘強)

The scenic Kashihara rice terraces of Kamikatsu are included in the top 100 terraced paddy fields of Japan.

How many types of garbage do you sort through at home? In Taiwan, having sorted 5 categories of household waste is quite an achievement. Yet, in the Japanese town of Kamikatsu in Tokushima Prefecture, the average household sorts waste into at least 7 and as many as 28 types!

In the mountain town of Kamikatsu, more than half of the residents are over 65 years old.

Located in Shikoku Region about an hour's drive from downtown Tokushima, Kamikatsu is 88% forest and home to over 1,500 residents living in 55 settlements at altitudes ranging from 100 and 800 meters. As many have moved out of town, Kamikatsu's senior population is as high as 52%, which means 1 in every 2 residents is over 65.

And yet, this agricultural town with many elders attracts nearly 2,000 visitors a year, of which 30% are from overseas. They are not here for the town’s picturesque landscape titled as “one of Japan's loveliest villages,” nor for the Kashihara rice terraces chosen as one of Japan’s top 100 terraced paddy fields. They are here to witness the town's zero-waste movement in action.

Kamikatsu’s residents need to bring their own garbage to the waste collection center and sort them accordingly.

What is so remarkable about the zero-waste movement in Kamikatsu? Let's look at their data. In 2003, Kamikatsu was Japan's first municipality to make a zero-waste declaration with a goal to eliminate waste without resorting to landfills or incinerators by 2020. (At present, of the over 100 cities worldwide that have made zero-waste declarations, 4 of them are in Japan.) The town’s recycling rate, at 81% in 2016 (Japan's average recycling rate is 20%), has for the past 5 years kept its ranking as one of the top 3 cities in Japan with less than 100,000 residents. The town's individual waste production per day is half of Japan's national average, and its waste management costs are 1/3 less.

Kamikatsu used to burn waste in the open and had also installed incinerators in the past, but these practices are no longer in place today. Residents are now responsible for managing their own refuse by transporting them to a waste collection center, and sort them into 45 waste categories. Their dedication in waste reduction for over 20 years has made Kamikatsu a world renowned zero-waste town.

Kamikatsu's Waste Collection Center

The sole waste management station in Kamikatsu features an astounding 45 waste categories. An open area with covered metal roofing, the center has 4 major areas—paper, plastic, metal, and glass bottles. Papers are further classified into 9 types, and plastics into 6 types. Common household items such as batteries, light bulbs, clothing, and furniture also have their designated sections for disposal. Garbage that cannot be currently processed and have to be incinerated or buried are placed in a special bag and stored in another area.

PAPERS: Paper or carton packaging and copy paper are placed in a paper bag first. Paper cartons are rinsed, dried, and dismantled. Paper rolls of plastic wraps and toilet paper are sorted separately as they have different processing methods.

PLASTICS: Plastics are further classified into 6 different types, including PET bottles, white polystyrene plates, expanded polystyrene materials, clean plastic bags, plastic caps, and other types of plastics. |

METALS: The caps of metal cans, aluminum cans, and pressure cans need to be removed first and sorted according to their material type. |

GLASS: Glass bottles and jars are also classified into several different types. |

OTHER: Cooking oil, lighters, blades, and pens each have their designated areas at the center. |

GENERAL WASTE: Waste that needs to be incinerated, such as used tissue paper, cigarette ash, and shoes, are disposed in a designated bin at the center. Residents can also purchase a specific bag to gather this type of garbage at home before bringing it to the center. |

No food waste or scraps are found at the center, for these are already composted at home. As food waste accounts for 30% of household garbage, the Kamikatsu municipal office offers subsidy for the purchase of an electric composter at 10,000 yen (about US$92). The compost can be spread on the field or left at the center for those who need it.

Sakano Akira, the current chair of Zero Waste Academy, left her job at a foreign corporation 5 years ago and moved to Kamikatsu, the hometown of her college classmate Azuma Terumi.

A woman carrying 2 bags of garbage to the center suddenly stopped to think about the wine bottle held in her hand. She was not sure which type of glass bottle it should belong. Seeing the waste collection center's director Kiyohara Kazuyuki come forward, she asked. "The bottle's body is translucent but its finish is transparent. Which type of glass bottle does it belong to?" "We can determine the type by the bottle's finish. If it's transparent, the bottle is considered as a transparent glass bottle.” With this new piece of information, the woman left the center with more clarity.

Commissioned by the municipal office of Kamikatsu, the non-profit Zero Waste Academy has been in charge of the management and operation of the town's waste collection center as well as the promotion of zero-waste practices since 2005. The fourth chair of Zero Waste Academy, Sakano Akira, who moved here 5 years ago, said, "Every visitor wanted to know how we have changed people's minds. And yet, it is never easy when it comes to shifting perspectives. There is no magic!"

There are no shortcuts to raising public awareness. Change can only happen with a comprehensive plan as well as slow and incremental paces. It cannot be achieved by simply creating a space with a bunch of bins and baskets lying around. Thoughtful efforts had to be in place for an organized approach to its operation.

Each sorting basket has an illustrated label that indicates the type of garbage, where and how it will be processed, and its costs or proceeds.

First, visual aids must be implemented to communicate the intended message. Each basket is clearly labeled with descriptions, indicating where and how the recyclables will be processed, along with its cost or proceeds. This is how people will know the whereabouts of their recycling efforts. If they think that all waste might still be incinerated in the end, it'll be difficult to successfully drive the zero-waste program," said Sakano.

When residents sort paper materials that are often disposed as general waste for incineration, they can collect points that can be exchanged for merchandise and daily necessities.

A points-system program to redeem merchandise has also been set up to engage residents in recycling efforts. The rewards program came about when the Zero Waste Academy found that much of resalable paper were disposed as general waste, accounting for 1/3 of the waste to be incinerated. Thus, the academy launched a rewards program to encourage the sorting and recycling of paper. Residents who separated paper from general waste could collect points to redeem goods. The program was later extended to include items that companies voluntarily collect for recycling and reuse, such as toothbrushes and detergent refill packages. In 2018, residents who chose not to use plastic shopping bags could also collect points through the program.

People, however, is what has driven Kamikatsu's success in its zero waste movement over the years. It's the residents who take their waste to the center, and the administrators who run the station.

Most Kamikatsu residents bring their household waste to the waste collection center while running errands.

Kamikatsu has never had a garbage truck, so residents need to transport their garbage to the waste collection center, a possible 40-minute car trip for those living far. Most residents take their garbage to the center when they leave home to run other errands. And for those without a car or unable to drive one, the municipal office provides a garbage pickup service once every 2 months.

The importance of the waste collection center lies in the fact that it is not only a place for garbage disposal; it also serves as an education center, open daily from 7:30 to 14:00, with 2 administrators working on site, providing assistance, support, and answers to the residents. Even though waste classification has been implemented for many years, new kinds of product packaging often result in many materials that are difficult to identify, or recyclables mistakenly disposed as general garbage for incineration. This is when the administrators can provide accurate information and timely support.

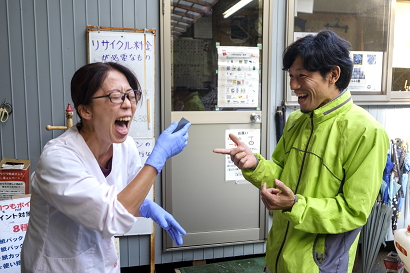

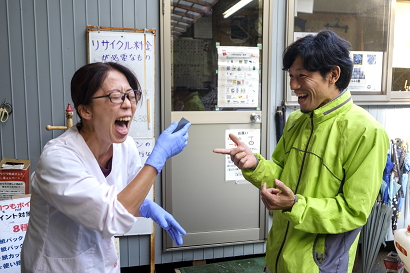

The director of Kamikatsu's waste collection center Kiyohara Kazuyuki (right) plays an important role in the local community. He not only informs and guides residents on how to sort their garbage, but also likes to joke around and make people laugh.

As queries are extensively varied, the center's administrators must be highly competent in their communication skills. Kiyohara Kazuyuki, an administrator at the center for the past 8 years, said he would adapt to different communication styles rather than sticking with one way of interacting with others. “As I become friends with the local residents, sometimes I don't even use honorific language with the elderly!” he said with a smile.

A Full Transformation of Waste Processing

“In the past, we simply burnt all our garbage. There was no sorting whatsoever!” recalled 71-year-old Katayama Hatsue, who was born and raised in Kamikatsu. It's hard to imagine that the garbage collection center was once a 6-meter-deep hole where residents dumped their garbage and burnt them in the open. The waste would burn the entire day, sending billows of black smoke into the air.

Most Kamikatsu residents carry their own reusable bottles.

After Japan implemented the Containers and Packaging Recycling Law in 1997, Kamikatsu started to classify garbage into 9 types and gradually added more classification types. As there were materials that no recycling companies would collect, the municipality installed 2 small incinerators in 1998, thus permanently ending the practice of open waste burning. However, as the dioxin emissions of the incinerators were higher than the emission standards of the Law Concerning Special Measures against Dioxins that came into effect in 2000, the town's 2 incinerators had to close down.

The municipality had to come up with a plan to process the town's waste. Both purchasing a large incinerator that met the standards or transporting all the waste out of town for incineration or landfill were too expensive for the small mountain village. In the end, the municipal office decided to fully promote the classification of garbage, expanding classification types from 22 to 35 in 2001. With more detailed classification, the town hoped that more recycling companies would be willing to purchase and collect the sorted materials.

The plan worked, and Kamikatsu drastically reduced the amount of waste that was transported out of town for incineration or landfill. The existing 45 types of waste are handed over to 10 recycling companies, of which 80% are turned into renewable resources and only 20% are left for incineration or landfill (such as PVC, rubber, diapers, etc).

According to Suga Midori, the environmental planning director at Kamikatsu's municipal office, the classification and recycling of the town's 286 tons of garbage cost 5.93 million yen (about US$54,000) in 2017. If sent for incineration or landfill, it would have cost 14.7 million yen (about US$134,000)—a whopping 60% savings in waste processing! In addition, the recycled metals and paper sold for 2.13 million yen (about US$19,400) further lowered the costs.

Katayama Hatsue, aged 71, lives in Kamikatsu with her husband, her daughter, and her son-in-law. They have 28 types of waste classifications in their home, with most types stored in the kitchen area such as bottle caps, clean plastics, and dirty plastics. |

Katayama's secret to recycling is to immediately clean it after each use. |

Waste classification surely served to relieve budget problems for the municipality; but for the town residents, the program brought fundamental changes in their daily lives. Katayama Hatsue's response to the town's program evolved from initial surprises to gradual acceptance. She used to see waste classification as troublesome, but now the practice has become part of her routine. In her household of four, there are 28 classification types of garbage. Pointing to the sorting bags of various sizes around her home, she jokingly said, “Isn't this like a garbage house?”

Katayama's secret to classifying waste is actually very simple. She doesn't pile up waste to deal with it later, but sorts and cleans garbage immediately after each use, “or the stress will be daunting.” For example, once she has finished the milk, she will rinse the carton and dismantle it for drying. After buying meat at the supermarket, she would immediately remove the polystyrene plate and plastic wraps, dispose them in the recycle bins at the supermarket, and put the meat in her own plastic bag. “This way, I have less garbage to deal with at home!” Katayama laughed. “But, my daughter thinks I'm such an embarrassment!”

While visiting her home, Katayama brought out refreshments and requested the unfinished sweets to be thrown away as general trash. Rather puzzled, I asked, "Shouldn't the sweets be classified as leftover food?” Katayama's answer was the last thing I would have expected as she covered her mouth with her hand and giggled. “Sometimes we need to break the rules!” Maybe such trivial acts of mischief can bring some ease and relaxation into her life.

Yamabe Yuka changes a cloth diaper for her 4-month-old daughter. She says that even though cloth diapers have to be washed by hand, they save money and are good for the environment.

A housewife who has moved to Kamikatsu 8 years ago, Yamabe Yuka was at first not used to all the waste classification requirements. "When I was still living with my parents, we simply sorted waste into combustibles, non-combustibles, and recyclable bottles. We didn't need to wash or rinse anything.” Now a mother of 3 children, she teaches her 6-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter how to classify garbage. “Both kids actually fight over going to the waste collection center!” For her daughter of 4 months old, Yamabe also got a cloth diaper kit from the municipal office. Compared to her older daughter who used disposable diapers and needed to be changed 5 times a day, Yamabe now needs to change her third child's cloth diapers 10 times a day. It's quite a hassle, but she has saved some money with cloth diapers.

The Hassle is What Makes It Worthwhile

From 90-year-olds to 19-year-olds, most Kamikatsu's residents had the same answers when asked about whether the zero-waste program is troublesome. “Of course it is troublesome…,” they would comment with a wry smile. There were people who also expressed that “since it is a regulation to classify, we just follow the rules and do it.” “If we do not do so, others may talk behind our backs…”

Thirty-one-year-old Azuma Terumi (first from left) returned to her hometown to open Cafe Polestar after graduating from college.

Owner of Cafe Polestar, Azuma Terumi, who returned to Kamikatsu 8 years ago, recalled that her mother used to say that the zero-waste practice would be meaningless if it was hassle-free. "The troublesome aspect of it will make people think more." Azuma quoted the words of her late mother Azuma Hitomi, who served as the environmental planning director of Kamikatsu, a figure instrumental in promoting waste classification and recycling during the early days.

Kozuki Yasunori, deputy director of the Research Center for Management of Disaster and Environment in Tokushima University, was impressed with Azuma Hitomi. “She isn't your typical civil servant. Several times she'd spend her own money to travel abroad and learn more about environmental policies!” Kozuki recalled that during the early days when the zero-waste program was up against hefty opposition, Azuma visited each of the 55 settlements across Kamikatsu to explain to its residents. She gained the support of some local elders, so the townspeople gradually came around.

Going zero waste means to reduce and prevent wastefulness. It not only focuses on processing waste; it aims to stop generating waste. Even though classification and recycling deals with waste that has already been generated, the process can still lead to changes in consumer behavior and less garbage production.

Kiyohara Kazuyuki has such kind of first-hand experience. Before moving to this town, he would simply discard the dirty drain sieve and replace it with a new one. But now, when he sees cheaply priced items at a shop, he'd think it over and check if he has similar items at home before buying stuff.

In Kamikatsu, food waste and scraps are processed at home. Residents can purchase an electric composter with subsidy from the municipal office.

In Azuma Terumi's case, she would bring a large container when buying bread to avoid using a disposable bag. Once, her 4-year-old son wanted to buy bread. “We didn't bring our container today, so we cannot buy it,” she told him. Much to her relief, her son not only didn't throw a tantrum, but even said thoughtfully, “Oh yes, that's right.”

The Pros and Cons of Cleaning Recyclables

Azuma Terumi also makes her own mayonnaise instead of buying a ready-made one. “If I buy ready-made mayonnaise, I'd have to separate the plastic cap, wash the plastic bottle, and leave them to dry. That's a lot of trouble! It's easier for me to make my own.” Of all the classifications, plastic items are the most troublesome for the residents. Plastic materials must be washed and dried to get rid of impurities and prevent mould in order to improve the quality of the material to be recycled. For plastic items that are difficult to clean, residents can dispose them into an area for dirty plastics at the waste center. Still, most residents wash plastic items before classifying them.

While washing helps with the recycling process, it also uses up water. “We have to be thankful for the abundant water resources in Kamikatsu that allow us to clean recyclable items.” Takeichi Takuya, a store owner who uses mountain spring water in his home, commented as he recounted a trip to India where he saw the lack of access to drinking water.

Kozuki Yasunori mentioned the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)—a method that assesses the environmental impacts throughout the life cycle of a product, process, or service. With LCA, the environmental impacts at every stage of processing waste can be taken into account when developing an adequate approach for the town's waste management. As Kamikatsu is blessed with abundant natural resources, washing recyclables before disposal doesn't burden their environment. But, this approach and system may not apply to other towns or places.

"The key is how we think about it. The number of classification types is only a means to the end." Fujii Sonoe, a promoter of the zero-waste program at Kamikatsu's municipal office, emphasised. Fujii went on to explain that after understanding the value and principles behind Kamikatsu's zero-waste movement, each place needs to find its most fitting waste management approach.

Cafe Polestar embodies the zero-waste lifestyle through its food and services. For example, it offers rice, tea, coffee beans, and sesame oil sold by weight, so customers can bring their own containers when purchasing the store's products. Leaves and flowers used to decorate the food served at the cafe are also locally grown.

Aiming for Sustainability

Kozuki Yasunori pointed out that going zero waste should not be Kamikatsu's ultimate goal. Sustainability, and serving as a role model in its environmental initiatives for other areas is at the core of it all. Kamikatsu's nearby towns of Kamiyama and Sanagochi have also made significant progress on waste reduction.

The interior decor at Rise & Win Brewing Co. features a chandelier made of used glass bottles and framed windows collected from Kamikatsu’s waste collection center.

Setting up a certification system for businesses is also a way to promote zero-waste practices. In 2017, the Zero Waste Academy launched a Zero Waste Accreditation for businesses aspiring to go zero waste. Currently, there are 12 accredited food and beverage establishments, including 5 that are located outside Kamikatsu. Businesses seeking certification participate in zero-waste training, set goals and plans, and receive accreditation on 6 categories—the use of local produce, adoption of reusable containers for product delivery, reduction of wasteful services, promotion of consumers' zero-waste practices, action in encouraging consumers to bring their own containers, and local reuse of resources.

Since junior high school, Azuma Terumi had decided that she would return to Kamikatsu one day, have a hip job, and raise children. Today, she is the owner of Cafe Polestar, with 5 accreditations under its belt, embodying the zero-waste lifestyle through its food and services.

The Rise & Win Brewing Company, also in Kamikatsu, is another restaurant with 5 accreditations. Its efforts in the local reuse of resources is quite remarkable, as can be seen in its decor using abandoned wooden boards, old window frames, and chandeliers made of used glass bottles—all of which have been collected from the town's waste center.

The company's president Tanaka Tatsuya said that when he opened the store 4 years ago, he hoped to combine beer, design and Kamikatsu's special characteristics to create a fun and cool place that attracts visitors. Now, his customers are mostly non-residents of Kamikatsu visiting from other places. When visitors ask about the store's unique decorations, the staff will share on the zero-waste movement so more people can learn about it.

At Zero Waste Academy's shop, there are clothes, stuffed animals and special money envelopes made by local elders from used kimono and koinobori (traditional carp-shaped windsocks).

In addition to food and beverage establishments, the Zero Waste Accreditation System has also added certification for businesses in the fashion sector, hoping to introduce zero-waste principles into an industry of mass production and enormous waste. At present, 2 clothing chains have received accreditation.

Given it is a year away before the 2020 deadline for Kamikatsu fulfilling its promise to the zero waste declaration, is it possible for the town to reach a recycling rate of 100% and achieve zero waste? "Unless there is a systemic change in governmental policies and business production, the remaining 20% would be an illusion,” responded Sakano openly.

Beverage vending machines are a significant source of waste in Japan.

Dilemmas of a Plastic-reliant Country

Japanese merchandises are famous for their beautiful designs, but this is often the result of excessive packaging—with the use of plastics in particular. With over 9 million tons of plastic waste per year, Japan is the world's second largest plastic user, only behind the U.S.

Japan used to ship its plastic waste abroad for many years. But recent bans in China and Southeast Asian countries to import foreign waste as well as an international implementation of controlling plastic imports and exports have served as a wake-up call to Japan of its own plastic crisis.

Each year, Japan produces about 30 billion plastic shopping bags. In July 2020, a ban on plastic shopping bags will be officially implemented, so supermarkets, convenient stores, and restaurants will no longer provide plastic bags for free. While plastic shopping bags account for only 2% of Japan's plastic waste, it is nevertheless an improvement.

Businesses have an important role to play in waste reduction, too. To implement zero waste from the source, the adoption of reusable materials and environmentally-friendly designs should be integrated at the product design and manufacturing stages. Only when a product design is fully connected to the product's eventual recycling can waste problems be truly addressed.

On my flight back to Taiwan, I watched Midsummer's Equation, a movie adapted from Higashino Keigo's novel. It explored the dilemma between environmental protection and resource development. In the film, Professor Yukawa Manabu pointed out, "While development destroys our natural environmental, humans also benefit from development. So, this is a matter of 'choices.' What we should do then? Once we see things clearly, we chose to do what should be done."

Be it troublesome, be it inconvenient, Kamikatsu's residents have chosen to embrace zero waste. What would be the path forward for the rest of us?

In Japan, domestic waste and business waste are collected separately. People need to bring their garbage to a designated location at specific times.

The scenic Kashihara rice terraces of Kamikatsu are included in the top 100 terraced paddy fields of Japan.

How many types of garbage do you sort through at home? In Taiwan, having sorted 5 categories of household waste is quite an achievement. Yet, in the Japanese town of Kamikatsu in Tokushima Prefecture, the average household sorts waste into at least 7 and as many as 28 types!

In the mountain town of Kamikatsu, more than half of the residents are over 65 years old.

Located in Shikoku Region about an hour's drive from downtown Tokushima, Kamikatsu is 88% forest and home to over 1,500 residents living in 55 settlements at altitudes ranging from 100 and 800 meters. As many have moved out of town, Kamikatsu's senior population is as high as 52%, which means 1 in every 2 residents is over 65.

And yet, this agricultural town with many elders attracts nearly 2,000 visitors a year, of which 30% are from overseas. They are not here for the town’s picturesque landscape titled as “one of Japan's loveliest villages,” nor for the Kashihara rice terraces chosen as one of Japan’s top 100 terraced paddy fields. They are here to witness the town's zero-waste movement in action.

Kamikatsu’s residents need to bring their own garbage to the waste collection center and sort them accordingly.

What is so remarkable about the zero-waste movement in Kamikatsu? Let's look at their data. In 2003, Kamikatsu was Japan's first municipality to make a zero-waste declaration with a goal to eliminate waste without resorting to landfills or incinerators by 2020. (At present, of the over 100 cities worldwide that have made zero-waste declarations, 4 of them are in Japan.) The town’s recycling rate, at 81% in 2016 (Japan's average recycling rate is 20%), has for the past 5 years kept its ranking as one of the top 3 cities in Japan with less than 100,000 residents. The town's individual waste production per day is half of Japan's national average, and its waste management costs are 1/3 less.

Kamikatsu used to burn waste in the open and had also installed incinerators in the past, but these practices are no longer in place today. Residents are now responsible for managing their own refuse by transporting them to a waste collection center, and sort them into 45 waste categories. Their dedication in waste reduction for over 20 years has made Kamikatsu a world renowned zero-waste town.

Kamikatsu's Waste Collection Center

The sole waste management station in Kamikatsu features an astounding 45 waste categories. An open area with covered metal roofing, the center has 4 major areas—paper, plastic, metal, and glass bottles. Papers are further classified into 9 types, and plastics into 6 types. Common household items such as batteries, light bulbs, clothing, and furniture also have their designated sections for disposal. Garbage that cannot be currently processed and have to be incinerated or buried are placed in a special bag and stored in another area.

PAPERS: Paper or carton packaging and copy paper are placed in a paper bag first. Paper cartons are rinsed, dried, and dismantled. Paper rolls of plastic wraps and toilet paper are sorted separately as they have different processing methods.

PLASTICS: Plastics are further classified into 6 different types, including PET bottles, white polystyrene plates, expanded polystyrene materials, clean plastic bags, plastic caps, and other types of plastics.

METALS: The caps of metal cans, aluminum cans, and pressure cans need to be removed first and sorted according to their material type.

GLASS: Glass bottles and jars are also classified into several different types.

OTHER: Cooking oil, lighters, blades, and pens each have their designated areas at the center.

GENERAL WASTE: Waste that needs to be incinerated, such as used tissue paper, cigarette ash, and shoes, are disposed in a designated bin at the center. Residents can also purchase a specific bag to gather this type of garbage at home before bringing it to the center.

No food waste or scraps are found at the center, for these are already composted at home. As food waste accounts for 30% of household garbage, the Kamikatsu municipal office offers subsidy for the purchase of an electric composter at 10,000 yen (about US$92). The compost can be spread on the field or left at the center for those who need it.

Sakano Akira, the current chair of Zero Waste Academy, left her job at a foreign corporation 5 years ago and moved to Kamikatsu, the hometown of her college classmate Azuma Terumi.

A woman carrying 2 bags of garbage to the center suddenly stopped to think about the wine bottle held in her hand. She was not sure which type of glass bottle it should belong. Seeing the waste collection center's director Kiyohara Kazuyuki come forward, she asked. "The bottle's body is translucent but its finish is transparent. Which type of glass bottle does it belong to?" "We can determine the type by the bottle's finish. If it's transparent, the bottle is considered as a transparent glass bottle.” With this new piece of information, the woman left the center with more clarity.

Commissioned by the municipal office of Kamikatsu, the non-profit Zero Waste Academy has been in charge of the management and operation of the town's waste collection center as well as the promotion of zero-waste practices since 2005. The fourth chair of Zero Waste Academy, Sakano Akira, who moved here 5 years ago, said, "Every visitor wanted to know how we have changed people's minds. And yet, it is never easy when it comes to shifting perspectives. There is no magic!"

There are no shortcuts to raising public awareness. Change can only happen with a comprehensive plan as well as slow and incremental paces. It cannot be achieved by simply creating a space with a bunch of bins and baskets lying around. Thoughtful efforts had to be in place for an organized approach to its operation.

Each sorting basket has an illustrated label that indicates the type of garbage, where and how it will be processed, and its costs or proceeds.

First, visual aids must be implemented to communicate the intended message. Each basket is clearly labeled with descriptions, indicating where and how the recyclables will be processed, along with its cost or proceeds. This is how people will know the whereabouts of their recycling efforts. If they think that all waste might still be incinerated in the end, it'll be difficult to successfully drive the zero-waste program," said Sakano.

When residents sort paper materials that are often disposed as general waste for incineration, they can collect points that can be exchanged for merchandise and daily necessities.

A points-system program to redeem merchandise has also been set up to engage residents in recycling efforts. The rewards program came about when the Zero Waste Academy found that much of resalable paper were disposed as general waste, accounting for 1/3 of the waste to be incinerated. Thus, the academy launched a rewards program to encourage the sorting and recycling of paper. Residents who separated paper from general waste could collect points to redeem goods. The program was later extended to include items that companies voluntarily collect for recycling and reuse, such as toothbrushes and detergent refill packages. In 2018, residents who chose not to use plastic shopping bags could also collect points through the program.

People, however, is what has driven Kamikatsu's success in its zero waste movement over the years. It's the residents who take their waste to the center, and the administrators who run the station.

Most Kamikatsu residents bring their household waste to the waste collection center while running errands.

Kamikatsu has never had a garbage truck, so residents need to transport their garbage to the waste collection center, a possible 40-minute car trip for those living far. Most residents take their garbage to the center when they leave home to run other errands. And for those without a car or unable to drive one, the municipal office provides a garbage pickup service once every 2 months.

The importance of the waste collection center lies in the fact that it is not only a place for garbage disposal; it also serves as an education center, open daily from 7:30 to 14:00, with 2 administrators working on site, providing assistance, support, and answers to the residents. Even though waste classification has been implemented for many years, new kinds of product packaging often result in many materials that are difficult to identify, or recyclables mistakenly disposed as general garbage for incineration. This is when the administrators can provide accurate information and timely support.

The director of Kamikatsu's waste collection center Kiyohara Kazuyuki (right) plays an important role in the local community. He not only informs and guides residents on how to sort their garbage, but also likes to joke around and make people laugh.

As queries are extensively varied, the center's administrators must be highly competent in their communication skills. Kiyohara Kazuyuki, an administrator at the center for the past 8 years, said he would adapt to different communication styles rather than sticking with one way of interacting with others. “As I become friends with the local residents, sometimes I don't even use honorific language with the elderly!” he said with a smile.

A Full Transformation of Waste Processing

“In the past, we simply burnt all our garbage. There was no sorting whatsoever!” recalled 71-year-old Katayama Hatsue, who was born and raised in Kamikatsu. It's hard to imagine that the garbage collection center was once a 6-meter-deep hole where residents dumped their garbage and burnt them in the open. The waste would burn the entire day, sending billows of black smoke into the air.

Most Kamikatsu residents carry their own reusable bottles.

After Japan implemented the Containers and Packaging Recycling Law in 1997, Kamikatsu started to classify garbage into 9 types and gradually added more classification types. As there were materials that no recycling companies would collect, the municipality installed 2 small incinerators in 1998, thus permanently ending the practice of open waste burning. However, as the dioxin emissions of the incinerators were higher than the emission standards of the Law Concerning Special Measures against Dioxins that came into effect in 2000, the town's 2 incinerators had to close down.

The municipality had to come up with a plan to process the town's waste. Both purchasing a large incinerator that met the standards or transporting all the waste out of town for incineration or landfill were too expensive for the small mountain village. In the end, the municipal office decided to fully promote the classification of garbage, expanding classification types from 22 to 35 in 2001. With more detailed classification, the town hoped that more recycling companies would be willing to purchase and collect the sorted materials.

Katayama Hatsue, aged 71, lives in Kamikatsu with her husband, her daughter, and her son-in-law. They have 28 types of waste classifications in their home, with most types stored in the kitchen area such as bottle caps, clean plastics, and dirty plastics.

The plan worked, and Kamikatsu drastically reduced the amount of waste that was transported out of town for incineration or landfill. The existing 45 types of waste are handed over to 10 recycling companies, of which 80% are turned into renewable resources and only 20% are left for incineration or landfill (such as PVC, rubber, diapers, etc).

According to Suga Midori, the environmental planning director at Kamikatsu's municipal office, the classification and recycling of the town's 286 tons of garbage cost 5.93 million yen (about US$54,000) in 2017. If sent for incineration or landfill, it would have cost 14.7 million yen (about US$134,000)—a whopping 60% savings in waste processing! In addition, the recycled metals and paper sold for 2.13 million yen (about US$19,400) further lowered the costs.

Katayama's secret to recycling is to immediately clean it after each use.

Waste classification surely served to relieve budget problems for the municipality; but for the town residents, the program brought fundamental changes in their daily lives. Katayama Hatsue's response to the town's program evolved from initial surprises to gradual acceptance. She used to see waste classification as troublesome, but now the practice has become part of her routine. In her household of four, there are 28 classification types of garbage. Pointing to the sorting bags of various sizes around her home, she jokingly said, “Isn't this like a garbage house?”

Katayama's secret to classifying waste is actually very simple. She doesn't pile up waste to deal with it later, but sorts and cleans garbage immediately after each use, “or the stress will be daunting.” For example, once she has finished the milk, she will rinse the carton and dismantle it for drying. After buying meat at the supermarket, she would immediately remove the polystyrene plate and plastic wraps, dispose them in the recycle bins at the supermarket, and put the meat in her own plastic bag. “This way, I have less garbage to deal with at home!” Katayama laughed. “But, my daughter thinks I'm such an embarrassment!”

While visiting her home, Katayama brought out refreshments and requested the unfinished sweets to be thrown away as general trash. Rather puzzled, I asked, "Shouldn't the sweets be classified as leftover food?” Katayama's answer was the last thing I would have expected as she covered her mouth with her hand and giggled. “Sometimes we need to break the rules!” Maybe such trivial acts of mischief can bring some ease and relaxation into her life.

Yamabe Yuka changes a cloth diaper for her 4-month-old daughter. She says that even though cloth diapers have to be washed by hand, they save money and are good for the environment.

A housewife who has moved to Kamikatsu 8 years ago, Yamabe Yuka was at first not used to all the waste classification requirements. "When I was still living with my parents, we simply sorted waste into combustibles, non-combustibles, and recyclable bottles. We didn't need to wash or rinse anything.” Now a mother of 3 children, she teaches her 6-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter how to classify garbage. “Both kids actually fight over going to the waste collection center!” For her daughter of 4 months old, Yamabe also got a cloth diaper kit from the municipal office. Compared to her older daughter who used disposable diapers and needed to be changed 5 times a day, Yamabe now needs to change her third child's cloth diapers 10 times a day. It's quite a hassle, but she has saved some money with cloth diapers.

The Hassle is What Makes It Worthwhile

From 90-year-olds to 19-year-olds, most Kamikatsu's residents had the same answers when asked about whether the zero-waste program is troublesome. “Of course it is troublesome…,” they would comment with a wry smile. There were people who also expressed that “since it is a regulation to classify, we just follow the rules and do it.” “If we do not do so, others may talk behind our backs…”

Thirty-one-year-old Azuma Terumi (first from left) returned to her hometown to open Cafe Polestar after graduating from college.

Owner of Cafe Polestar, Azuma Terumi, who returned to Kamikatsu 8 years ago, recalled that her mother used to say that the zero-waste practice would be meaningless if it was hassle-free. "The troublesome aspect of it will make people think more." Azuma quoted the words of her late mother Azuma Hitomi, who served as the environmental planning director of Kamikatsu, a figure instrumental in promoting waste classification and recycling during the early days.

Kozuki Yasunori, deputy director of the Research Center for Management of Disaster and Environment in Tokushima University, was impressed with Azuma Hitomi. “She isn't your typical civil servant. Several times she'd spend her own money to travel abroad and learn more about environmental policies!” Kozuki recalled that during the early days when the zero-waste program was up against hefty opposition, Azuma visited each of the 55 settlements across Kamikatsu to explain to its residents. She gained the support of some local elders, so the townspeople gradually came around.

Going zero waste means to reduce and prevent wastefulness. It not only focuses on processing waste; it aims to stop generating waste. Even though classification and recycling deals with waste that has already been generated, the process can still lead to changes in consumer behavior and less garbage production.

Kiyohara Kazuyuki has such kind of first-hand experience. Before moving to this town, he would simply discard the dirty drain sieve and replace it with a new one. But now, when he sees cheaply priced items at a shop, he'd think it over and check if he has similar items at home before buying stuff.

In Kamikatsu, food waste and scraps are processed at home. Residents can purchase an electric composter with subsidy from the municipal office.

In Azuma Terumi's case, she would bring a large container when buying bread to avoid using a disposable bag. Once, her 4-year-old son wanted to buy bread. “We didn't bring our container today, so we cannot buy it,” she told him. Much to her relief, her son not only didn't throw a tantrum, but even said thoughtfully, “Oh yes, that's right.”

The Pros and Cons of Cleaning Recyclables

Azuma Terumi also makes her own mayonnaise instead of buying a ready-made one. “If I buy ready-made mayonnaise, I'd have to separate the plastic cap, wash the plastic bottle, and leave them to dry. That's a lot of trouble! It's easier for me to make my own.” Of all the classifications, plastic items are the most troublesome for the residents. Plastic materials must be washed and dried to get rid of impurities and prevent mould in order to improve the quality of the material to be recycled. For plastic items that are difficult to clean, residents can dispose them into an area for dirty plastics at the waste center. Still, most residents wash plastic items before classifying them.

While washing helps with the recycling process, it also uses up water. “We have to be thankful for the abundant water resources in Kamikatsu that allow us to clean recyclable items.” Takeichi Takuya, a store owner who uses mountain spring water in his home, commented as he recounted a trip to India where he saw the lack of access to drinking water.

Kozuki Yasunori mentioned the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)—a method that assesses the environmental impacts throughout the life cycle of a product, process, or service. With LCA, the environmental impacts at every stage of processing waste can be taken into account when developing an adequate approach for the town's waste management. As Kamikatsu is blessed with abundant natural resources, washing recyclables before disposal doesn't burden their environment. But, this approach and system may not apply to other towns or places.

"The key is how we think about it. The number of classification types is only a means to the end." Fujii Sonoe, a promoter of the zero-waste program at Kamikatsu's municipal office, emphasised. Fujii went on to explain that after understanding the value and principles behind Kamikatsu's zero-waste movement, each place needs to find its most fitting waste management approach.

Cafe Polestar embodies the zero-waste lifestyle through its food and services. For example, it offers rice, tea, coffee beans, and sesame oil sold by weight, so customers can bring their own containers when purchasing the store's products. Leaves and flowers used to decorate the food served at the cafe are also locally grown.

Aiming for Sustainability

Kozuki Yasunori pointed out that going zero waste should not be Kamikatsu's ultimate goal. Sustainability, and serving as a role model in its environmental initiatives for other areas is at the core of it all. Kamikatsu's nearby towns of Kamiyama and Sanagochi have also made significant progress on waste reduction.

The interior decor at Rise & Win Brewing Co. features a chandelier made of used glass bottles and framed windows collected from Kamikatsu’s waste collection center.

Setting up a certification system for businesses is also a way to promote zero-waste practices. In 2017, the Zero Waste Academy launched a Zero Waste Accreditation for businesses aspiring to go zero waste. Currently, there are 12 accredited food and beverage establishments, including 5 that are located outside Kamikatsu. Businesses seeking certification participate in zero-waste training, set goals and plans, and receive accreditation on 6 categories—the use of local produce, adoption of reusable containers for product delivery, reduction of wasteful services, promotion of consumers' zero-waste practices, action in encouraging consumers to bring their own containers, and local reuse of resources.

Since junior high school, Azuma Terumi had decided that she would return to Kamikatsu one day, have a hip job, and raise children. Today, she is the owner of Cafe Polestar, with 5 accreditations under its belt, embodying the zero-waste lifestyle through its food and services.

The Rise & Win Brewing Company, also in Kamikatsu, is another restaurant with 5 accreditations. Its efforts in the local reuse of resources is quite remarkable, as can be seen in its decor using abandoned wooden boards, old window frames, and chandeliers made of used glass bottles—all of which have been collected from the town's waste center.

The company's president Tanaka Tatsuya said that when he opened the store 4 years ago, he hoped to combine beer, design and Kamikatsu's special characteristics to create a fun and cool place that attracts visitors. Now, his customers are mostly non-residents of Kamikatsu visiting from other places. When visitors ask about the store's unique decorations, the staff will share on the zero-waste movement so more people can learn about it.

At Zero Waste Academy's shop, there are clothes, stuffed animals and special money envelopes made by local elders from used kimono and koinobori (traditional carp-shaped windsocks).

In addition to food and beverage establishments, the Zero Waste Accreditation System has also added certification for businesses in the fashion sector, hoping to introduce zero-waste principles into an industry of mass production and enormous waste. At present, 2 clothing chains have received accreditation.

Given it is a year away before the 2020 deadline for Kamikatsu fulfilling its promise to the zero waste declaration, is it possible for the town to reach a recycling rate of 100% and achieve zero waste? "Unless there is a systemic change in governmental policies and business production, the remaining 20% would be an illusion,” responded Sakano openly.

Beverage vending machines are a significant source of waste in Japan.

Dilemmas of a Plastic-reliant Country

Japanese merchandises are famous for their beautiful designs, but this is often the result of excessive packaging—with the use of plastics in particular. With over 9 million tons of plastic waste per year, Japan is the world's second largest plastic user, only behind the U.S.

Japan used to ship its plastic waste abroad for many years. But recent bans in China and Southeast Asian countries to import foreign waste as well as an international implementation of controlling plastic imports and exports have served as a wake-up call to Japan of its own plastic crisis.

Each year, Japan produces about 30 billion plastic shopping bags. In July 2020, a ban on plastic shopping bags will be officially implemented, so supermarkets, convenient stores, and restaurants will no longer provide plastic bags for free. While plastic shopping bags account for only 2% of Japan's plastic waste, it is nevertheless an improvement.

Businesses have an important role to play in waste reduction, too. To implement zero waste from the source, the adoption of reusable materials and environmentally-friendly designs should be integrated at the product design and manufacturing stages. Only when a product design is fully connected to the product's eventual recycling can waste problems be truly addressed.

On my flight back to Taiwan, I watched Midsummer's Equation, a movie adapted from Higashino Keigo's novel. It explored the dilemma between environmental protection and resource development. In the film, Professor Yukawa Manabu pointed out, "While development destroys our natural environmental, humans also benefit from development. So, this is a matter of 'choices.' What we should do then? Once we see things clearly, we chose to do what should be done."

Be it troublesome, be it inconvenient, Kamikatsu's residents have chosen to embrace zero waste. What would be the path forward for the rest of us?

In Japan, domestic waste and business waste are collected separately. People need to bring their garbage to a designated location at specific times.

Contact Us | Plan a Visit | Donate

8 Lide Road, Beitou 11259, Taipei, Taiwan

886-2-2898-9999

005741@daaitv.com

©Tzu Chi Culture and Communication Foundation

All rights reserved.