The Story of Chinese New Villages in Malaysia

By Lai Ying-qi (賴英錡)

Photos by Alberto Buzzola (安培淂)

Abridged and translated by Andrew Huang (黃執虔)

Shawn Chang (張牧軒)

Rosalind Chang (張薰云)

The Story of Chinese New Villages in Malaysia

By Lai Ying-qi (賴英錡)

Photos by Alberto Buzzola (安培淂)

Abridged and translated by

Andrew Huang (黃執虔)

Shawn Chang (張牧軒)

Rosalind Chang (張薰云)

The family of Zhu You Lai (朱有來) has been living in Seri Kembangan, formerly known as Serdang New Village, in Malaysia since the era of British colonial rule.

If you walk along the streets in the village, you will see a mixture of western-style houses and wooden plank houses. Elderly people sit in front of their houses and enjoy their time with their grandchildren while youngsters play together beside the roads. It's a peaceful and tranquil scene of country life. However, about 70 years ago, this place was once under heavy surveillance and plagued with poverty.

Back in 1942, Japan launched the Pacific War, defeating the British colonial government in Malaysia within six months, and started a cruel reign that lasted three years and eight months. During that period of ongoing war, the British army chose to collaborate with the Communist guerrillas, mostly comprised of Malaysian Chinese, to battle against the Japanese army.

After the war, the British government returned to Malaysia in an attempt to restore its colonial reign. However, as the British Empire was already on the verge of collapse after World War II, the United Kingdom's poor financial status made it unable to govern Malaysia efficiently. In addition, the idea of national self-determination also swept over post-war Malaysia. After several fruitless negotiations with the British government, the Secretary General of the Communist Party of Malaya, Chin Peng (陳平), started an armed anti-British movement.

Old photo of Tanjong Sepat New Village

A former member of the Communist Party of Malaya who wishes to remain unnamed lamented, "Back then, the Communist Party retreated to forests and initiated guerrilla warfare against the Japanese army, contributing immensely to the post-war independence of Malaysia. However, they were later labeled "terrorists" by the British and the Malaysian governments, which was really unfair."

To effectively combat the Communist Party of Malaya, the British government declared martial law in Peninsular Malaysia in 1948. In the following year, it launched the "Briggs' Plan," a policy that rounded up the Malaysian Chinese scattered all over the countryside into specific areas that had a strict entry-and-exit policy. The purpose of doing so was to prevent the Malayan Communist Party from getting supplies from those Chinese people. According to the statistics of the Malaysian Chinese Museum, a total of 452 of such villages exist in Malaysia. They are called "Chinese new villages."

Old Time Tales from the New Villages

"The British used wire to fence up an area and rounded up all nearby Malaysian Chinese residents into it. Each village had only a few gateways that led outside. It was like living in a chicken cage," Ampang New Village resident Grandma Li Gui Mei (李桂妹) recalled, "You could go outside to work after 6 a.m. in the morning and you must return before 6 p.m. Most of the residents here were farmers, tin miners or rubber tappers. If you came back after 6 p.m., you would be denied access into the village."

Li Gui Mei (李桂妹) holds in her hands the wooden pan she used for tin panning when she was young.

The 79-year-old Li Gui Mei grew up in a Chinese new village. She started doing tin panning at the age of 10 to support her family and raise the younger children in her household. Malaysia was rich in tin resources. Many male villagers would go out to work as tin miners. They used water from lakes to separate tin gravel from the rocks. The used water would then gather into small creeks or ponds, and the female villagers would take their wooden pans and go to those creeks or ponds to do tin panning in hopes of making some extra money.

Li Gui Mei said with a smile, "Skill is very important in tin panning. If you are not skillful, you won't obtain any tin gravel no matter how long you try. Back then, a kilogram of tin gravel could sell for over 10 Malaysian ringgits (around US$ 2.45 in modern times). That was enough to buy three days' worth of food."

After the tin mines were exhausted, locals used the tin mining ponds for fish farming. Edible fishes were sold to nearby markets. Ornamental fishes, such as tropical fishes and carps, would be exported to Japan as they could be sold at higher prices.

"Back then, it was like we were living in a concentration camp! When you entered or exited the village, the security guards would do a body search on you. We were not allowed to take rice, flour, sugar or salt out of the village in order to prevent the Malayan Communist Party from obtaining those supplies," Former chief of Lawan Kuda New Village, Lee San Choy (李新才), said, "But there were some nice Malaysian guards who would occasionally allow villagers to take a meal's worth of pastry with them as their lunches."

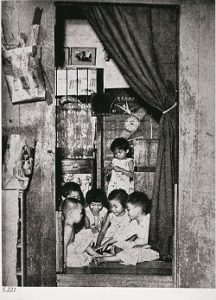

A family of nine that lived in a small and crowded wooden house inside a new village.

Chen Wen Zhi (陳文治), former general affairs administrator of a local temple at Jinjang New Village, now an 80-year-old grandpa, said, "After the British government relocated people into the new villages, they allocated land to each household according to the number of people in it. A family with more than seven people would receive two pieces of land while a family with less than that would receive one piece of land. As for building materials for the houses, they gave each family two wooden boards only, and people had to find the rest of the necessary materials by themselves. Most households removed wooden boards from their original homes and used them to build the wooden houses inside the new villages."

Cai Ri Chang (蔡日昌), a resident of Sungai Siput Selatan New Village who was born in 1942, has lived through the Japanese occupation, the era of British martial law and the civil war between the Malaysian government and the Malayan Communist Party. He recalled, "Apart from forbidding us to take foodstuffs such as rice and flour out of the village, we couldn't bring food from the outside into the village either. A family would need a government-issued rice certificate to buy rice at grocery stores. What if you got hungry when you were working outside the new village? For tin miners, mining companies would prepare large pots of cooked food, and workers would eat together by the mines."

As Sungai Siput Selatan New Village was located in a mountain area, it was surrounded by mountains, which once served as perfect hideouts for Communist guerrillas. "My uncle was a Communist! I once went into the mountains to visit him before the establishment of Sungai Siput Selatan New Village. Later on, maybe because they ran out of food and supplies, he decided to leave the mountains and turn himself in to the British army. In the end, he was sent back to his hometown Hepo in Chaozhou, China. We didn't see each other for the next 70 years."

Cai showed us a short video on his cell phone. "A few years ago, we went to China to visit him. By that time, he was already 94 years old. But his memories of those years of fighting against the British and Japanese armies remained fresh and vivid. He could even still speak a little Malay."

Being forced to be separated from his family for decades might be a sorry fate, but his situation was still much better than that of other members of the Malayan Communist Party who lost their lives. "In order to warn the villagers not to get involved with the Communist Party, police officers even put corpses of Communist Party members on public display right next to the police office."

Cai continued, "In truth, there really were Communist Party members living in the village, masquerading as ordinary villagers in order to gather intelligence. Your next-door neighbor might happen to be a Communist. People said that the government also sent spies into the mountain region to infiltrate the Communist Party. All in all, it was like living in a spy movie during that period; the whole village was enveloped in an atmosphere of tension and distrust."

Migrating to Southeast Asia to Seek One's Fortune

Gopeng Heritage House is a museum that displays antiques and items that bear witness to the history of Malaysian Chinese.

"Actually, not all Malaysian Chinese were forced to move into the new villages," Pang See Kong (彭西康), a researcher of culture and history, said, "Gopeng, for example, was a town that became prosperous because of its tin mining industry. The wealthy Malaysian Chinese businessmen there could choose to stay in town." He then pointed out that the Kinta Valley region, which includes Gopeng, Ipoh and Kampar, used to be the world's leading tin producing region, accounting for over half of the world's tin production.

"Around the 1920s and 1930s, a Chinese man named Mo Peng (毛兵) came to Southeast Asia to seek his fortune and discovered the rich tin mines in Gopeng. He then recruited his Chinese fellowmen to come here and turn this wasteland of swamps and forests into a comfortable town. However, it was Eu Kong (余廣) and Eu Tong Sen (余東旋) that really propelled Gopeng into prosperity."

"Eu Kong opened the Eu Yan Sang Chinese Herbal Pharmacy to provide relief to the medical needs of the tin miners in case of illness. His son Eu Tong Sen took things even further. He not only inherited his father's pharmacy, but also recruited tin miners and went into the tin mining business, and also served as a tax collector of the British government. In time, he even expanded his business into other regions and countries. Today, in Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur, and even in Hong Kong and Singapore, one can still see streets named 'Eu Tong Sen Street' in his honor."

After coming to Malaysia, Chinese people from different provinces of China often went into different occupations too. Hakka and Cantonese people mostly became tin miners while people from Hainan mostly became coffee shop owners.

Two men sit in front of their home in Bukit Koman New Village. Their father used to be a miner.

People from different provinces also spoke different languages. After living in new villages together for a long time, the residents gradually learned to speak each other's languages, and now most of them can communicate with each other in Cantonese and Hakka. In addition, residents introduced their hometowns' traditional dishes such as Kon Loh Mee (Cantonese dry noodle) and Hainanese chicken rice into Chinese new villages. They also made some local modifications to the original recipes. For example, Hakka stuffed tofu is a classic Hakka dish. However, after it was introduced into Malaysia, people substituted local fish for pork as stuffing, giving the dish a new spin.

The Days after the Martial Law

In 1957, Malaysia declared independence as a nation; the martial law was gradually lifted during the 1960s. The residents of new villages regained their freedom, no longer living a prison-like life. Although their standard of living was still far from affluent, they began to have some forms of entertainment in the villages.

The Malaysian Chinese-owned tin mining companies would stage Cantonese operas in front of the temple of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva on the bodhisattva's birthday. As a gesture of appreciation towards the hard work of their employees, those companies would also hold outdoor movie screenings of Western cowboy movies in the villages. The villagers would take their rattan chairs to the screening events and sit together to watch the movies.

"I remember that the crime rate was very low in the village when I was young, and villagers were mostly humble and decent people. There was no need for any household to lock the door of its house to shut out thieves, because everyone was equally poor and there was nothing to steal. Also, our relationship with each other was really close. Almost everyone knew everyone. You could even run a tab if you didn't have enough money to pay for things at the grocery store," Jinjang New Village resident Chen Yi Xing (陳儀興) said with a smile, "Of course, if you did something bad, the news would spread around the village in no time, too!"

Jinjang New Village is the biggest Chinese new village in Malaysia, boasting more than 60,000 residents. A central street divides the village into northern and southern areas. It features an elementary school and a middle school. The three adjacent temples at the entrance of the village―Feng Shan Si, Nan Yang Gong and Fu Ze Temple—were villagers' religious centers. "Jinjang and Zyun Sek Movie Theaters were young people's usual hangouts back then," Chen added.

Apart from tin mines, Malaysia also has gold mines. Bukit Koman New Village in Raub District was once very prosperous due to the gold mining industry. After the British companies left, some Australian companies stayed in Bukit Koman and continued the gold mining operation. "At that time, the Aussies hired many Malaysian Chinese as gold miners and mined a lot of gold. Many miners smuggled out small blocks of gold and made a small fortune out of them," Hakka pastry shop owner Zhang Si Sheng (張思勝) smiled and said, "At that time, teahouses and gambling houses were everywhere. Good food, alcohol, prostitutes and gambling—all available. It was a place that never slept."

Hu Jin Huo (胡金伙) was once a mining truck driver. He is the village's last surviving resident who has lived through the era of gold mining.

The 90-year-old Grandpa Hu Jin Huo (胡金伙) is the new village's last surviving resident who has witnessed that period of time, which was a time of prosperity and indulgence. "In the beginning, I was just a handy boy in the mining area; later, I became a mining truck driver." Because of the frequent occurrence of mine collapses, flooding or lung diseases caused by inhaling too much marsh gas, many miners had a pessimistic and hedonistic mindset. "Miners spent their hard-earned money on gambling and entertainment. They didn't mind dissipating all their money, since they could earn it back in a few days," said Hu.

As gold prices fluctuated in the 1960s, the gold-mining Australian company finally decided to pull out, causing the once thriving town to gradually lose its former glory.

In the 1980s, the oversupply of tin and rubber caused their prices to plunge in the international market. Many new village residents who worked as miners or rubber tappers lost their jobs. Moreover, under the global trend of urbanization, many young people from new villages migrated to big cities such as Kuala Lumpur and Johor Bahru, or even to other countries such as Taiwan, Singapore and European countries to seek their fortunes, leaving their elderly parents and children behind in the new villages.

"You can't deny that new villages are mainly occupied by elderly people nowadays," Chen Kong Hoy (曾廣海) said, "In order to revitalize our new village, we launched a new village transformation initiative, in which we distributed arabica coffee fruits to residents of our new village and encouraged every household to grow coffee in front of its house. That way, the elderly could have something to occupy themselves with, and they could also make some extra income out of it." He also planted a lot of coffee trees in the village's Mandarin elementary school and middle school, and let students of those schools take care of the coffee trees, so they could learn the life cycle of a coffee tree.

"We are also planning to promote coffee culture and create a brand for our village through cultural festivals, and combine the coffee industry of our village with tourism," Chen said, adding that the ultimate goal of all those endeavors is to create employment opportunities so that young people from his village can return to their hometown and make a living there.

Bearing Witness to the History of Malaysian Chinese

Born in Bukit Koman New Village, internationally acclaimed Malaysian Chinese film director Wong Kew Lit (黃巧力) has directed a series of documentaries about Chinese new villages, including the widely acclaimed My New Village Stories (2009).

Renowned photographer Kim Teoh (張榮欽) took part in organizing the Karnival Rakyat Machang Bubuk in 2017, which breathed new life into the age-old village.

His documentary film The New Village, premiered in 2013, was banned because its content involved the Malayan Communist Party. However, the issue of Chinese new villages has gotten more and more attention from the public. In December 2017, the Karnival Rakyat Machang Bubuk (literally "Machang Bubuk People's Carnival") was held in Machang Bubuk New Village. Renowned photographer Kim Teoh (張榮欽), who was born in that new village, was invited to take part in organizing the event. He gladly accepted the invitation as he had always wanted to do something for his hometown. The festival featured a photo exhibition, a travel forum, and a photography competition.

From the war-torn era of World War II to the highly restrictive life under the martial law, and from the prosperity after the lift of the martial law to the decline in the 1980s caused by the collapse of the tin mining industry, Chinese new villages have quietly borne witness to the story of Malaysian Chinese.

To the younger generation of Malaysian Chinese growing up in the cities, the term "new village" may no longer bear any sense of familiarity. However, they should still remember the difficult time the older generation went through in the past, for although they lived in poverty and harsh conditions, the close tie they shared with each other made new villages their true home. Chinese new villages not only witnessed the torments Malaysian Chinese went through in the past, but also the spirit of resilience and unity they displayed in the face of those torments.

Maybe it's just as what Kim Teoh said: "No matter how big the world is, there will always be a home named 'new village' that awaits your return."

Contact Us | Plan a Visit | Donate

8 Lide Road, Beitou 11259, Taipei, Taiwan

886-2-2898-9999

005741@daaitv.com

©Tzu Chi Culture and Communication Foundation

All rights reserved.