A Lifetime of Dedication to Traditional Embroidery

By Lai Ying-qi (賴英錡)

Photos by Yan Song-bo (顏松柏)

Abridged and translated by Andrew Huang (黃執虔)

Syharn Shen (沈思含)

A Lifetime of Dedication to Traditional Embroidery

By Lai Ying-qi (賴英錡)

Photos by Yan Song-bo (顏松柏)

Abridged and translated by

Andrew Huang (黃執虔)

Syharn Shen (沈思含)

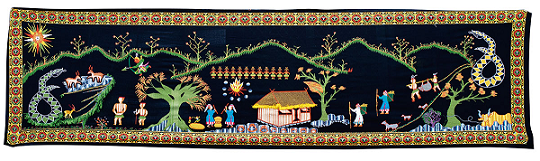

Lavaus and her embroidered artworks display Paiwan cultural motifs and patterns. Featuring tribesmen, flowers, earthenware pottery, and hundred-pacer snakes, the still figures on the pieces tell the story of her tribe.

In the silent darkness, on a lush-green and flowery lawn, orange-red faces surround a gold-yellow sun, and brown-black hundred-pacer snakes are coiled on dark blue clay pots. These embroidered motifs on a large tapestry seem to narrate an ancient Paiwan legend: “A long, long time ago, the Sun God laid two eggs, and each fell into a separate clay jar. Two hundred-pacer snakes guarded and cared for the two eggs, and when they hatched, a prince of the Paiwan tribe was born from one, and from the other, an innocent and beautiful princess.”

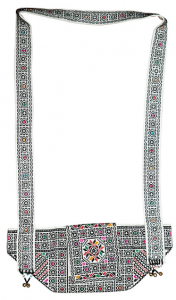

Paiwan mothers would knit bags for their children to carry betel nuts or dried tobacco leaves.

This large and stunning tapestry was embroidered by Lavaus (陳利友妹), who humbly said that the piece was created by accident. Having tried out different patterns and arrangements throughout more than sixty years of embroidery making, Lavaus didn’t want to throw away unfinished or less-than-ideal pieces, and on a whim, she wove all the scattered pieces together into this beautiful and breath-taking art piece.

An Embroidery Career of Sixty Years

Lavaus is an expert at the craft of Paiwan embroidery. With gray hair at the age of 75, she remains energetic, with her eyes completely absorbed on the fabric and her fingers weaving back and forth with ease and agility as she demonstrates the techniques of Paiwan embroidery. In the blink of an eye, on a piece of black cloth that seemed plain at first, beautiful patterns suddenly emerge.

Reminiscing about her childhood, Lavaus said there was a big tree by her home. The women from the tribe would gather under the tree to embroider and chat about their daily lives. Her mother would always bring her to the gatherings, and with time, she picked up basic embroidery skills. After graduating from elementary school, Lavaus started doing embroidery work to support her family’s income. At the age of 16, she went to learn tailoring and pattern making, but she remained fascinated about Paiwan embroidery, along its brilliant colors and intricate needlework. “In the first few years after I got married, I was busy taking care of my kids and also moved to Kaohsiung because of my husband’s work, so I stopped doing embroidery for a while,” Lavaus said. “It wasn’t until my husband got very sick and we returned to my hometown in Taimali did I pick up embroidery again.”

As the Paiwan people value social order and hierarchy, only the nobility could use motifs of clay pots and hundred-pacer snakes.

During that difficult period of time in her life, she supported her family by running a small grocery store while taking orders to make traditional costumes, hats, and bags with Paiwan embroidery motifs. Though her made-to-order works were well received by her customers, she only saw embroidery as her hobby rather than a potential career that could lead to success. Day after day, she simply continued to do what she was passionate about. Her neighbors have made cynical remarks, saying that embroidery was no big deal and could not make profit as one could earn more money by working in the city. Lavaus never paid attention to these comments and just kept on doing what she loved.

Things turned out like the famous quote from the classic Bollywood film 3 Idiots: “Pursue excellence, and success will follow.” Lavaus kept on learning and polishing her craft until success finally came knocking on her door. As sales of her embroidery works increased, life improved for Lavaus and her family, and with the advice from a friend, Lavaus closed her grocery store and founded a workshop. Now that she could earn a living through doing what she loved, Lavaus devoted her life to embroidery.

The Sun God, ancestral spirits, and shamans are motifs that could only be worn by the Paiwan nobility.

In 2003, a friend helped her enter the Taiwan Craft Competition, which is considered “the Oscars” of Taiwan’s craft industry. A bit reluctant at first, Lavaus said that her works were plain and ordinary, and that other competitors were outstanding masters of their craft. Little did she know that she would be chosen as the winner of “The Dream of Craft” theme award for that year. Later on, Lavaus was further honored by the National Taiwan Craft Research and Development Institute for her outstanding achievement in Paiwan traditional embroidery. Acclaimed as a national treasure, Lavaus was even consulted on the culture of Paiwan embroidery by researchers who came all the way from Japan to gather data for anthropological research.

The Unique Features of Paiwan Embroidery

With bright and colorful patterns on a black fabric, Lavaus’ award-winning work Welcoming Gods, Worshipping Ancestors, and Celebrating the Harvest Year features in its center clay pots and hundred-pacer snakes that symbolize the legendary origins of the Paiwan tribe. By the sides stand members of the nobility clad in fine and beautiful costumes, warriors carrying hunted wild boars, and ordinary people dancing in celebration. “Through embroidery, I want to tell my childhood memories of the harvest festivals,” Lavaus explained. “Apart from the famous Maleveq Festival held once in five years, the Paiwan people also have an annual harvest festival to thank the gods and our ancestral spirits for their protection over the year. In the annual festivals, after receiving gods and ancestral spirits, people dance as a way to make offerings to them and pray for blessings.”

On the elegant and elaborate patterns on her artwork, Lavaus points out that “all motifs have different meanings. A sun represents the Sun God, which symbolizes power. Human heads represent ancestral spirits and signify protection. Hunting knives and animals refer to warriors, and cross-shaped patterns are symbols for shamans, who can ward off evil. Butterflies represent innocent young girls whereas flowers and grass refer to ordinary people. Divided into social classes, the Paiwan people value social order and hierarchy. Only the nobility are allowed to use certain motifs such as the Sun God, hundred-pacer snakes, and clay pots.”

Lavaus’ works are inspired by her memories of tribal life, including landscapes of Mount Taimali, her tribe’s gathering place, people dancing to celebrate the harvest festival, warriors going hunting in the mountains, etc. Her works also feature religious and worship motifs such as the Sun God and hundred-pacer snakes.

When Lavaus was little, she had asked her mother why the pretty figures and patterns could only be worn by the tribal chief and the nobility. “Because we respect our tribe’s order, hierarchy, and tradition,” was her mother’s response, vividly remembered after all these years. As Lavaus grew up, she had come to realize that the embroidered patterns are not simply meant to be beautiful, but even more importantly, to convey the moral values and cultural tradition of the Paiwan tribe.

Because of her widespread fame in the art of embroidery, friends from the Amis and Puyuma tribes have asked Lavaus if she could help create traditional costumes for them. She always declined, explaining that “different tribal patterns and colors have different meanings. I only understand Paiwan motifs. Since I don’t understand other tribes’ traditions, it’s not wise for me to mess with them. I simply want to do my best with Paiwan embroidery.” Her words show her respect for the embroidery traditions of other indigenous groups as well as her determined focus on her own roots.

For example, the hundred-pacer snake is an important motif and symbol for both the Paiwan and Bunun people. For the Paiwan, the hundred-pacer snake enjoys a high social status, so motifs of it can only be used by the tribal chief and the nobility. But for the Bunun, the hundred-pacer snake shares the same social status as the tribesmen and is regarded as a close friend by the people, so anyone can use its motifs. The patterns on indigenous clothing do not only display aesthetic beauty, but also convey the cultural values and traditions of each indigenous group.

By integrating fashion and traditional art, Liu Yan-xi and Lavaus hope to promote the art of embroidery.

On important ceremonies, the Paiwan people always wear their most elaborate costumes. Lavaus said that in the past, one could tell a person’s social position just by observing the patterns on their costumes. She also pointed out that Paiwan women needed to learn embroidery skills so she could make clothes for her family. “When children grew up and were about to get married, their mothers would personally create traditional costumes for them.” Lavaus added that “it was also easier for a girl who possessed great embroidery skills to win the hearts of young men.” But when asked if a girl with poor embroidery skills might worry about not being able to marry off, Lavaus laughed and said, “It’s not that strict. If a girl doesn’t have good embroidery skills, she can trade her other skills with someone who is good at it.”

She said that life in the tribe used to be very simple as there wasn’t much exchange of money and people bartered goods and services. One would embroider or weave a basket for someone who’d in turn help harvest fruits, vegetables, or millet. People would help each other out and interactions between tribesmen were friendly and harmonious. “Actually, embroidery is not difficult. Even without talent, one can learn it with diligent practice. The key lies in whether one has patience and concentration,” concluded Lavaus earnestly.

Saving the Disappearing Art of Traditional Embroidery

A typical scene of an indigenous woman embroidering on a piece of cloth is fading away. With changes in time and the advent of industrialization, embroidery is no longer considered a necessary skill and virtue for indigenous women. Despite displaying the beauty and cultural tradition of indigenous art, embroidery is often regarded as hard work that is arduous, unprofitable, and unrewarding. Fewer people are willing to learn it, and traditional embroidery is in danger of disappearing.

Lavaus has over thirty years of experience teaching embroidery.

To pass on her embroidery skills, Lavaus has been travelling around Taiwan for the past thirty years to teach in schools and communities. Her students range from students to women, and from indigenous people to the Hakka and the Hoklo people. Lavaus laughs as she says, “Embroidery is no longer for girls only. Some boys do it better!”

Lavaus emphasized her point again, saying that “embroidery techniques are not difficult. The real problem is that the young generation today has not experienced the traditional tribal life of the early days. Yet, the creation of patterns and the matching of colors depend heavily on the artist’s memories and emotional attachment to tribal life. Taking myself for example, I take inspiration from the mountain and sea landscapes of my hometown in Taimali, my childhood memories of the harvest festivals, Paiwan traditional stone houses, etc.” Whenever she creates new patterns or designs, Lavaus always displays her works publicly and is happy to share with those who want to learn it. Having never registered for intellectual property rights, Lavaus added: “The passing on of traditional embroidery is what is truly important.”

With a faint sense of helplessness, Lavaus admits that the passing on of traditional culture is a long and difficult path. With her single efforts, she cannot save the traditional art of embroidery from disappearing. And as she ages with time, she’s not sure whether she has enough strength to keep on carrying this heavy responsibility. Fortunately, a group of young people has brought fresh hopes to Lavaus.

Through embroidery, Lavaus records her childhood memories of her tribe and hometown.

Trained in fashion design and with knowledge in Italy’s fashion industry, Liu Yan-xi (劉妍希) moved her clothing store from Taipei to Taidong County in eastern Taiwan seven years ago. Not long after, she was introduced to Lavaus and decided to help sell her works and creations. “I deeply admire her fine and elaborate craftsmanship. The beautiful patterns that she has created should not simply disappear, and we should let more people see the beauty of Paiwan’s embroidery art,” Liu said.

Liu also helps young people develop their careers through a non-profit platform that she established. From this platform, a group of young women from different parts of Taiwan have gathered, and they also learn embroidery from Lavaus, who treat these young women as her own granddaughters. “I’ve never made embroidery before, and she’s always patient and kind in teaching me step by step.” Shi Yuan-chen (施垣辰) shares what she has learned from Lavaus. “In addition to embroidery, I’ve also learned wisdom in life from her.” The wisdom is Lavaus’ persistence and optimism in the face of life’s trials.

Since Lavaus’ workshop in her hometown is too small, Liu is preparing a larger space in Taidong County to showcase all of Lavaus’ embroidery works over the years as well as her personal collection of cultural artifacts from her tribe. Liu hopes that through this exhibit, Lavaus can tell her story to the public.

Lavaus, wearing a Paiwan traditional costume.

Once a required skill for indigenous women, embroidery was also a means to express their emotions. Amidst clouds and mists hanging over high mountains, a graceful wife would make a set of clothes embroidered with elaborate patterns for her husband to wear when he went out hunting. A young girl would also create beautiful embroidery to reveal her unspoken love to someone she admired.

Though indigenous languages have no writing systems, the colorful patterns on traditional costumes serve as hieroglyphs that silently record a tribe’s story and culture. But the ancient wisdom and tradition of indigenous tribes is on the verge of disappearing in the face of modernization. Fortunately, Lavaus stands firmly against all odds, devoting her life not in search of fame or fortune, but with the sole wish of preserving and passing on the rare and precious art of traditional embroidery.

Lavaus spreads out before her an unfinished work of art—a large piece of black cloth embroidered with the mountain landscapes of Mount Taimali and her childhood memories of tribal life. “My ultimate goal for the rest of my days is to finish this piece. On it, I want to embroider everything about my hometown and all the stories of my tribe, so our future generations can continue to witness the beauty of Paiwan embroidery,” says Lavaus, with strong determination in her eyes.

Contact Us | Plan a Visit | Donate

8 Lide Road, Beitou 11259, Taipei, Taiwan

886-2-2898-9999

005741@daaitv.com

©Tzu Chi Culture and Communication Foundation

All rights reserved.